"We

met on an elevator she was getting on, I was getting off."

What really happened, of course, was a little more complex--elevators,

unless broken, being unlikely places for extended introductions.

"We

met on an elevator she was getting on, I was getting off."

What really happened, of course, was a little more complex--elevators,

unless broken, being unlikely places for extended introductions.

"We

met on an elevator she was getting on, I was getting off."

What really happened, of course, was a little more complex--elevators,

unless broken, being unlikely places for extended introductions.

"We

met on an elevator she was getting on, I was getting off."

What really happened, of course, was a little more complex--elevators,

unless broken, being unlikely places for extended introductions.

Roger Davis and a friend were on their way to a commercial interview in New York when they saw the tall, beautiful brunette. Both stopped short, but it was Roger's companion who did the about-face and walked right back into the elevator. And 45 minutes later, when Roger reappeared, he was still standing in the lobby trying to talk her into a date.

As it turned out, that first persistent suitor never did convince her to say yes. Roger did.

It was the first of two romantic robberies in a courtship that lasted only weeks yet managed to cross continents.

Soon, the leading lady was on her way to the European set of "The Adventurers." Tied down by his various roles in TV's "Dark Shadows," Roger stayed behind. It didn't take long, however (days in fact), before he realized that he not only missed, but wanted to marry her, and so the daytime occult villain unhinged his fangs and headed for the airport.

Boy meets girl, boy loses girl, boy gets girl. To the chagrin of "The Adventurers" producers, the off-screen script continued its inevitable course. Roger wouldn't leave Rome unless Ellen left with him. She did--they did--and a week later were married in Houston, Texas.

While Leigh Taylor-Young took over the "Adventurers" part, Ellen Smith's parents adjusted to the shock.

Roger still marvels at their reaction. "Considering how suddenly we were engaged," he says, "they were really understanding. They're very loving people, and they have a great deal of faith in their daughter, so they just went ahead with the ceremony."

It may

have been the first such occasion when the groom was more starry-eyed

than the bride. For unlike many of his contemporaries, Roger loved

the idea of marriage. "It may just go back to my provincial

upbringing," he admits now, "but I never thought about

living any other way.

It may

have been the first such occasion when the groom was more starry-eyed

than the bride. For unlike many of his contemporaries, Roger loved

the idea of marriage. "It may just go back to my provincial

upbringing," he admits now, "but I never thought about

living any other way.

"And I don't think either of us anticipated any of the problems involved--in any marriage. Probably nobody would get married if he knew how difficult it is. People tell you it will be, your parents tell you, but you never believe them. You always say, ‘Yeah, but we're in love--not like you guys.' I can remember my dad saying, ‘Love? What the hell is love? You talk like you've cornered the market on love!'

"But I'd never met a girl like Ellen before," Roger continues. "She was so innocent, unspoiled. She was born to be a wife, too--and I'm not saying that as any kind of put-down. I guess what I mean is it just makes it easier to choose that kind of girl to marry."

Despite her recognized dancing talent (she was first brought to N.Y. by George Balanchine for his City Ballet) and a highly successful career in TV commercials, Ellen's professional interests remain in the background. Success on a public scale seems to offer little allure; she prefers to remain on the outskirts of showbusiness, leaving the more ambitious realm to Roger.

Three

years later, he still wonders at her old-fashioned qualities.

"Ellen sees the bright side of everything," he says.

"That's good, because I can't. She makes me appreciate that

work isn't everything."

Three

years later, he still wonders at her old-fashioned qualities.

"Ellen sees the bright side of everything," he says.

"That's good, because I can't. She makes me appreciate that

work isn't everything."

And he needs that kind of support now more than ever.

On January 1, while in Denver doing commercial voice-overs for a new ski are, Roger received a phone call simultaneously informing him that Peter Duel committed suicide and offering him the role of Hannibal Heyes in "Alias Smith and Jones."

Clearly, it was an opportunity for stardom that left Roger with no feelings of joy or triumph.

"The question at that point," he remembers the call, "was not to come and take over, but simply to complete the shows for that season. It was: "Who's going to put his head on the chopping block for "Alias Smith and Jones"?

"I'd been the series' announcer since it began, and had also done a couple of guest spots on the show, so they knew me and thought I would be good."

To some, it was a rather brutal dismissal of the young man who had originated the co-starring role, and Roger soon found himself the object of criticism. But to anyone involved in television production, the network's "go ahead" decision was not so shocking.

"The series was already running late," Roger explains. "They were putting together episodes that would be aired one week later. The scripts were written, and considering the time problem, couldn't be rewritten.

"Then, too, there were other people's livelihoods at stake--an entire production crew--at a time when Hollywood isn't the easiest place to find work. These people had families to worry about, and would have been a big blow had the series been dropped that suddenly.

"Of course, the viewers who felt really close to Peter, who were his close fans, were insulted and won't watch," Roger sympathizes, "but I think most of the people who enjoy the show are happy the decision was made and can understand the dilemma.

"As for me--my sadness about Pete's death has nothing to do with my taking over his role; my sorrow is a personal thing. This is a good part, it's work, and took it.

"And

two days after I started doing he show, Pete's brother Geoff came

down to the set to talk to me. He said that he and the rest of

the family wanted me to know that Pete had talked to them about

me several times, which was unusual since he apparently didn't

bring up other actors very often. Geoff wanted me to know that

Pete's family understood that it was a good part and a good break

for me. They didn't want me to feel in any way upset by taking

it."

"And

two days after I started doing he show, Pete's brother Geoff came

down to the set to talk to me. He said that he and the rest of

the family wanted me to know that Pete had talked to them about

me several times, which was unusual since he apparently didn't

bring up other actors very often. Geoff wanted me to know that

Pete's family understood that it was a good part and a good break

for me. They didn't want me to feel in any way upset by taking

it."

Although Roger and Peter were not close friends, they had worked together and occasionally saw each other socially, and Roger had observed signs of depression in the young actor.

"The closer you were to Pete, the more you worked with him, the less surprising his suicide would be," Roger ventures. "He was visibly troubled, although this never interfered with his work in front of the cameras. In the end, his professional talent would always surmount any personal turmoil he felt at the moment. He was a real pro."

There has been speculation that Peter's drinking led to his death, but Roger feels alcoholism was only part of the star's problem.

"I never saw him drunk; lots of people who knew him never saw him drunk, although there were always lots of beer cans around his house. But it was like a joke. I'd walk in and say, ‘Hey, Pete-- who drinks all the beer?,' and he'd say, ‘I don't know--I never empty the garbage,' or ‘The maid never picks them up.'

"I don't think, however," Roger continues, "that Pete would have killed himself if he hadn't been drunk at the time. If he'd been sober, I think the reality of what he was doing would have been enough to prevent it.

"But the drinking, his work frustration, were really just symptomatic of what was really troubling him, and I think to get to that you'd have to talk to the women who knew him. He only became really close to girls; I'm not sure even Geoff knows why he did it. It was obvious that he was going under, that he wanted everybody's help, was asking for help. And everybody tried to help, wanted to, but it was hard to know how."

Like everyone who knew Peter, Roger is still troubled by the suicide, saddened by a tragedy that seemed peculiarly inevitable. "Pete was a genuinely good person who just got lost," he says. "In the end, there is nothing more to say."

Today, a regular viewer of the series probably sees Hannibal Heyes as a combination of both actors. But there are vast differences in the off-screen lives of the two men, beginning with their early backgrounds.

"We grew up in opposite worlds," Roger says. "Pete came from a doctor's family, where life was rather gentle and restrained. I was raised in a horse-racing milieu where there was a lot of noise and story-telling. It was almost a carnival atmosphere."

Roger was born on April 15, 1940 in Louisville, Kentucky. [CJC's Note: Based on what I've read elsewhere, I suspect a couple of years have been shaved off of this date.] Today, he writes and produces commercials for his father's tire company, and still pays visits to the family's horse farm.

"Everyone in my family is very easygoing," Roger says. "The best way I could describe them is: If I came home tomorrow and said, ‘Hey, I've just been elected President,' they'd probably look at me and say, ‘Well, sure hope you have a job in four years.'"

The middle of three brothers, Roger was sent away to military school at the age of 11. It's the kind of experience most boys would resent; curiously, Roger enjoyed the confinement.

"It was the first chance I'd had to be me," he explains. "At military school, families didn't exist, everybody was equal, and you could create your own standards for judging people. And it wasn't all that tough; there was always an underlying sense of fairness.

"For example," Roger remembers with glee, "there was the time I threw Cadet Lavett out the second story window of Bullard Hall, (Cadet Lavett was known as 'Bullethead,' by the way.)

"The incident was reported, and I had go before the head of the school, Col. Ingram. The Colonel looked down at the report and said, ‘Mr. Davis, it says here you've been reported for throwing Cadet Lavett out of the second story window of Bullard Hall.' He paused, then asked very gravely, ‘Did you do that, Mr. Davis?'

"‘No, Sir, I did not,' I lied, knowing full well that in military school your word is your bond.

"The Colonel looked down at the paper, crossed out the report, and looked back.

"'Well, why didn't you, Mr. Davis?' he asked me. 'Cadet Lavett's needed something like that for a long time.'"

Another culture shock was in order when Roger left the Tennessee military academy for New York City and Columbia University: "I got to Columbia and looked at all those busts on the top of the library--Homer, Plato, Aristophenes--and I was so dumb, I thought they'd all graduated from Columbia."

Four years later, however, he was smart enough to get admitted to Harvard Law School--which he left after one week to enroll at UCLA. And two years after that, he was just beginning to teach freshman English when he won a part in ABC-TV's "Gallant Men." Eight roles in "Dark Shadows," the lead in the stage play, "McBird" and numerous TV guest roles followed--until "Alias Smith and Jones" and steady employment.

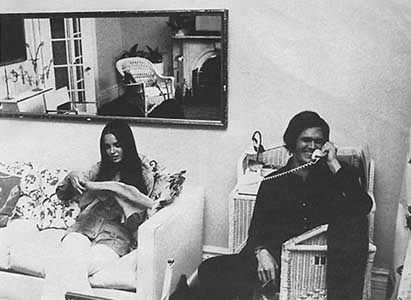

But with the Western breakthrough, there has been some necessary confusion in the Davis marriage. Ellen (who works under the name Jaclyn Smith) pursues her modeling, career in the East: Roger's "Alias" role means months on location in Hollywood and Utah. There's less time to be together, and Roger admits they'll have to work to combat the career conflicts that trouble many showbusiness couples.

When they do meet, however, their I marriage still boasts some of the glamorous, romantic aura begun in courtship. A dream of many wives--dinner out every night--is a reality for Ellen. "We both work so hard," Roger explains, "that I think it's unfair to ask her to cook. I've always wondered how men could put that burden on their wives--to know that they've been working all day, too, and then expect them to come home and slave over a hot stove. And since I don't feel like doing it, either, we go out. It doesn't always have to be someplace elaborate--in fact, our favorite restaurant is a pizza parlor.

A crazy way to run a marriage? Maybe.

But one admiring friend doesn't think so. "Both Roger and

Ellen have their own interests," he says, "so they don't

need a domestic routine. She models; takes ballet lessons--has

a life of her own as well as one with him. That's good for any

marriage, and something they really need now, it may seem strange,

but I think it's all these differences that will keep them from

falling apart."

Back to Articles List