By Cecil Smith

Roy

Huggins subscribes to the theory that television exists in only

two eras of time--now and the western. The only truly successful

exception to the rule, he said, was the bloody Untouchables,

set in the ‘20s.

Roy

Huggins subscribes to the theory that television exists in only

two eras of time--now and the western. The only truly successful

exception to the rule, he said, was the bloody Untouchables,

set in the ‘20s.

Roy

Huggins subscribes to the theory that television exists in only

two eras of time--now and the western. The only truly successful

exception to the rule, he said, was the bloody Untouchables,

set in the ‘20s.

Roy

Huggins subscribes to the theory that television exists in only

two eras of time--now and the western. The only truly successful

exception to the rule, he said, was the bloody Untouchables,

set in the ‘20s.

Moreover, Roy feels the period of the western is a rigidly circumscribed block of time between the end of the Civil War and the first distant backfire announcing the 20th century.

"What makes the western so attractive," he said, "is that it operates in the purest kind of freedom. There are no restrictions. Have you noticed money is rarely used in westerns? Men belly up to the bar and drink but nobody pays.

"When you complicate it with automobiles, telephones, the accoutrements and gadgetry of our lives, you add restrictions. It becomes something else.

And yet one of the most blockbuster westerns of modern times in box office terms is the movie "Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid," which is of this century and the decline of the West as far as the freedom to rove and rob was concerned and one of its most memorable scenes involves a gadget--a bicycle.

There's reason to believe that "Cassidy" opened the door to the development of such latter-day TV westerns as the forthcoming Nichols with James Garner and The Big Wheels with Rod Taylor, both set in the period just before World War I. Even though Nichols stars Garner, whose career was launched by Huggins with Maverick, and The Big Wheels is by Doug Heyes, a Huggins protege, Roy has little faith in either project.

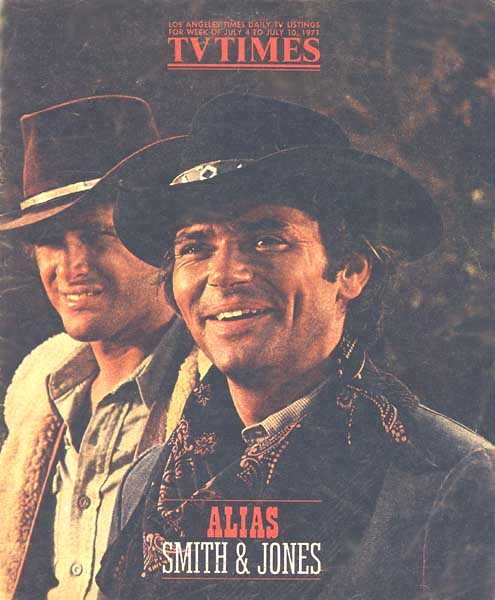

But then Roy insists that Alias Smith and Jones, his current western, is traditional as to period--1880, not 1900. And he denies that it was spawned by the success of "Butch Cassidy." This is hard to swallow. The series seems almost a spinoff of the movie with Pete Duel and Ben Murphy as Smith and Jones (on the cover) almost the precise counterparts of the outlaws weary of outlawing and desiring amnesty that Paul Newman and Robert Redford played on the big screen.

Huggins

can argue sources with you, tracing themes back to the Elizabethans

and the Greeks, the frontiers of literature. He feels Smith and

Jones is a lineal descendant of two of his TV creations, Maverick

and The Fugitive; he is executive producer and a frequent writer

on Smith and Jones but the series is the brain child of its young

producer, Glen A. Larson.

Huggins

can argue sources with you, tracing themes back to the Elizabethans

and the Greeks, the frontiers of literature. He feels Smith and

Jones is a lineal descendant of two of his TV creations, Maverick

and The Fugitive; he is executive producer and a frequent writer

on Smith and Jones but the series is the brain child of its young

producer, Glen A. Larson.

Roy readily admits that he has seen TV theories he regarded as infallible blow up in his face. For instance he says he always thought television was "Little Orphan Annie Time" where no one ever grew old, time never really passed.

"But when we did Run for Your Life, I made the mistake of telling the audience that our hero, Ben Gazzara, had only two years to live," he said. "When we started our third year, they stopped watching us. They no longer believed the show. We had irreparably damaged their faith...

"Either that or we became too abrasive for them in the third year. We found the series adapted itself well to exploring social and controversial themes. But I think that loss of faith was primary."

To prove his point, he cited some of the more abrasive studies he's done on The Lawyers, exploring social evils and exposing them, and said there's been no loss of popularity through such heavy going. Like television, Roy exists in two eras of time--the western and now. The Lawyers, with Burl Ives, Joe Campanella and James Farentino, a full partner in The Bold Ones with the death of The Senator, is Huggins' "now".

An incredibly prolific man, he supplies almost every story on his series. Of the first 14 episodes of Smith and Jones, 12 were by Thomas John James; that byline was on seven of the eight Lawyers last season. By no coincidence. Roy Huggins has three young sons named Thomas, John and James.

Over the last 15 years since he came into television with Cheyenne, Maverick and 77 Sunset Strip, it is doubtful if any one person has provided so much diversion to so many people around the world as Roy Huggins. He says it's hard to keep good people like Mike Ritchie in television--they leave to do movies. Huggins never leaves. Why?

"There are too many mediocre movies being made now," he says.

A college professor is what he wanted

to be and he has the scholarly look and the quick, inquisitive

mind of a teacher. His brother Jack teaches at the University

of Arizona and is, Roy says, "the happiest man I know."

Roy returned to UCLA a few years ago to get his doctorate and

teach but quit--"Too tough," he said, and went back

to spinning celluloid dreams.

Back

to Articles List