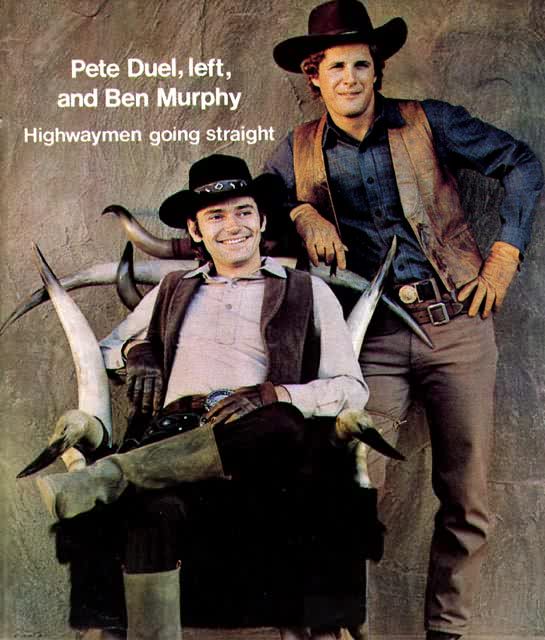

IT'S REALLY ALIAS BUTCH CASSIDY AND THE

SUNDANCE KID

by Cecil Smith (Hollywood)

The Telegram (Toronto) TV Weekly, February 5, 1971

For the first time since television took the pledge

to eschew crime and violence for the straight and narrow path,

a new western series is upon us.

For the first time since television took the pledge

to eschew crime and violence for the straight and narrow path,

a new western series is upon us.

It's about two thieves named Smith and Jones who eschew crime and violence for the way of righteousness, but I'm sure the similarity is only coincidental.

You see, these cats have a helluva time making it straight, while the networks piously protest they still keep crime and violence far from their doors.

Pete Duel, who plays Smith to Ben Murphy's Jones, objects to the word "thieves." He says: "We're more like highwaymen." I said: "Do you rob banks?" and he said: "Yeah, and trains." I said: "You're thieves." He said: "Well, we're trying to go straight.

"You see," Pete continued, "this is set in the 1890s when the law was getting too tough for a bank robber to make out, so we've been promised amnesty by the government if we'll give up robbery."

I asked: "Like Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid?"

Pete said: "No. Not exactly. We're not really bad guys. I don't think this character I played ever shot anybody." Butch Cassidy? "Though Jones is a gunny, he's got a reputation." The Sundance Kid!

At any rate, the series arrived Jan. 21, replacing Matt Lincoln and facing the formidable Flip Wilson who gunned down Lincoln, even with Vince Edwards in the part.

There was a preview to the series when ABC's Movie of the Week offered Alias Smith and Jones as its 90-minute prototype. Along with Duel and Murphy, the movie had Susan St. James, Earl Holliman, Forrest Tucker and James Drury aboard.

Though he was not concerned with the movie, the series is being produced by Roy Huggins who devised Maverick a decade ago and has been trying to get the networks to let him do another western comedy ever since. He wrote and produced the prototype for one last season called the Young Country, also involving Duel, which didn't sell as a series.

Huggins quite properly casts his gunmen as gamblers, which was their primary occupation despite the myths. Duel says this character, Smith (or Hannibal Heyes) has a way with cards and seems to "lust for the tables."

"This whole thing happened so fast I don't know him very well yet," said Pete. "We have to kind of find him as we go along."

This is Duel's third series. He was a

regular on Gidget and co-starred with Judy Carne in Love on a

Rooftop. He comes from a family of doctors in Rochester, N.Y.,

the first one to turn actor--"I was so bad in college I think

they were happy I found a profession other than medicine."

He came here in the road company of "Take Her, She's Mine" with Tom Ewell, stuck around to try and get a series. Since Love on a Rooftop folded, he's been conscientiously trying to avoid doing another one--"which is tough at Universal; you've got to be an artful dodger." But he says he's happy with Smith and Jones--"if I did another series, I wanted it to be a western."

Pete came to Universal with the promise he could do drama, not the sort of light comedy he'd been playing. He got his wish, some fine, gutsy parts, notably in a Marcus Welby and as Casey Poe in the recent World Premiere, The Psychiatrist: God Bless the Children.

So beautifully did he define Poe, a junky paroled to psychiatrist Roy Thinnes, that the character was continued in an episode of the series made from the movie which will be the fourth offering of Four-in-One next month.

"That was a real, three-dimensional character, one you could really get inside and play," said Pete. "It's not often you get really complex people to do in television. Here was a guy who was a hophead, but he could turn on the charm, pull out the stops and lie his way through anything."

And now he's got himself a charming thief

to play. Did I say thief? Highwayman. Who wouldn't hurt a hair

on your head.

Rick DuBrow, syndicated columnist, in his review

of the Smith and Jones telefilm, said Alias Smith and Jones, while

frankly similar to Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, was also

funny on its own, a well conceived tale of two outlaws who feel

modern times are catching up with them and try, with difficulty,

to get out of the bandit business.

What was provocative and potentially significant about Alias Smith and Jones, however, was not the 90 minute tale itself, but the fact that it was simply an introduction to an hour weekly series. If successful, the regular series version could mark a pivotal change in long-dormant video western.

Funny westerns are not new for video. ABC had a big hit years ago with Maverick. But it has been some time since television has had a new and successful western, for several reasons. One is that there was a sharp cutback on video violence after the killings of Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King and networks just avoided new westerns.

Another reason is that most traditional television frontier epics appeal mainly to middleaged and older viewers, and networks want the young audience also now. The problem here, some video people feel, is that old-style westerns may just not make contact with young viewers because, as one executive puts it, "They are ancient history. World War I and World War II are the westerns of the younger generation."

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid solved

the generation problem with its cool, hip, contemporary tone puncturing

the traditional western form. It's only logical that Alias Smith

and Jones jumped on the bandwagon. Happily, it succeeded in rollicking

fashion. If the series clicks, it could give video westerns new

life.

Back to Articles

List