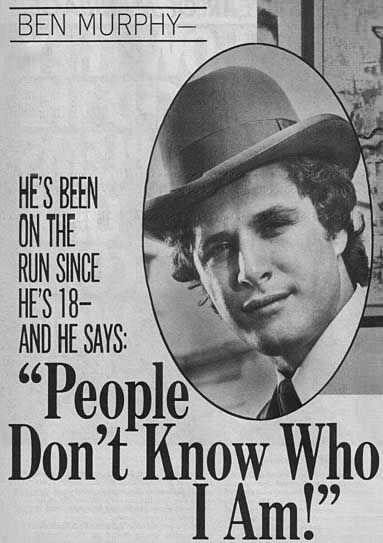

- BEN MURPHY--HE'S BEEN ON THE RUN SINCE

HE'S 18--AND HE SAYS:

- "PEOPLE DON'T KNOW WHO I AM!"

By Brooke Scott

- TV Radio Show, September 1971

"Image?"

said Ben Murphy. "I'm probably going to come off as a swinger,

a guy who digs broads; the whole bit." He pushed his Eggs

Benedict, forked up a mouthful and chased it with a hungry pull

on a bottle of beer. Murphy, alias Jed "Kid" Curry

of Alias Smith and Jones was lunching in the Universal

commissary and discussing the vagaries of the acting profession.

"Of course, right now," he allowed, "I don't have

an image. But if the show holds I suppose they'll nail one on

me. I probably won't like it." But he'll go along with it

anyway.

"Image?"

said Ben Murphy. "I'm probably going to come off as a swinger,

a guy who digs broads; the whole bit." He pushed his Eggs

Benedict, forked up a mouthful and chased it with a hungry pull

on a bottle of beer. Murphy, alias Jed "Kid" Curry

of Alias Smith and Jones was lunching in the Universal

commissary and discussing the vagaries of the acting profession.

"Of course, right now," he allowed, "I don't have

an image. But if the show holds I suppose they'll nail one on

me. I probably won't like it." But he'll go along with it

anyway.

In line with most of Hollywood's "overnight

success stories" Murphy has been around town for years, working

regularly in both films and television. It's a good face, but

the name meant nothing. Then ABC cast him as a gun-happy highwayman

in "Alias" and gave him the push he needed.

"The only thing I know," Ben

said, still on the subject of image, "is that it won't be

me, because I only show the surface to most people. The only time

I open up is with my friends. A woman will get to me and I'll

want her to know me. Still, I'm wary, because I hate women at

the same time I love them. I know they can hurt me. There's that

fear that they'll get to me..."

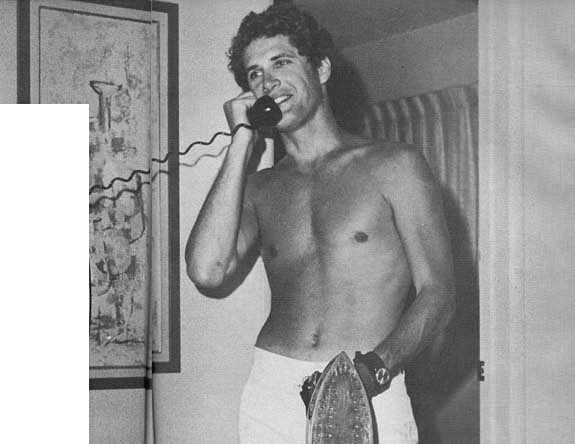

No one can blame them for trying. Some

people say Ben reminds them of a younger Paul Newman. There is

a resemblance in the blonde hair, blue eyes, and the mouth. And

they both like beer. Off-screen, Ben wears rimless Air Force-type

glasses. He's more powerfully built than Newman, the result of

an addiction to athletics. He skiis, swims, plays tennis, rides

horses--well.

He's been on the run since he was 18;

running away from home, his middle class background, from women,

from possessions. "I'm a loose floating soul," he grins,

"I've got a great big fear of being tied down to anything

or anybody."

He talks about his youth spent in Hinsdale,

Illinois where his parents still live and operate a clothing store.

It's a sketchy discourse. There are obviously tender spots. He

doesn't invite anything but cursory analysis.

"Everything goes back to my childhood,"

he says. "I was alone a lot because my parents always worked.

I was in nursery school as a very young child. At home, I learned

to enjoy my own mental processes and daydreams. I learned not

to really care too much about other people. My mother wasn't possessive,

quite the contrary. And I blamed her for a lot of things."

Ben caught himself. "Of course, I've long since forgiven

her."

"By the time I became a teenager,"

he continued, "the pattern was there. I was alone in my basement

room all the time during my four years in high school, reading,

doing my own thing. I never played around with the guys, with

cars, all that routine. I got involved with sports but never with

groups of people. Actually it was good for me. It made me what

I am today. It means I didn't go off and do the normal things

like being a doctor, a lawyer or an Indian chief living in the

suburbs--that whole bit.

"It's funny," Ben talked on.

"It's like this guy who is coming to see me today. I went

to high school with him and I haven't seen him since. Suddenly

he calls and wants to come by. Actually I never really gone along

with him one way or the other. I went clear through high school

and nobody ever paid any attention to me. Now, all of the sudden

I'm a big thing." This is surely not uncommon.

Ben downed the last of his beer and signaled

for another. "Naw, people don't both me too often. Most people

don't know who I am in the first place, and secondly they don't

know how to get hold of me. Yeah," he grinned. "I've

got a telephone. I even get obscene phone calls once in a while."

He laughed, and it did nice things to his face. The blue eyes

flashed, and I asked him if he is basically a happy person.

"I'm not the kind of guy who goes

around glowing," he replied, "but psychologically, I'm

happy. I talk a good happiness. Emotionally I go the full range

every day from anger to dejection to paranoia to happiness. I

don't try to level it off. It's good for me.

"It's why I became an actor in the

first place. I was stagnating emotionally. I just couldn't get

anything out. But all those years of acting classes, when I went

through hell as I began to learn about myself; that did it. On

top of this, I'll admit I have a need to be loved by everybody.

EVERYBODY! I mean I will seek out the person in a room who doesn't

like me and try to change this mind. Forget the people who do.

I'll go to the one who doesn't and work on him until he likes

me or I know why he doesn't."

Conversely Ben insists he doesn't need

individual friendships. "Because in never had them as I was

growing up," he explains. "I want to know that a person

likes me, but I don't want to be tied to them and I don't want

to have to do anything in return. But I do want a woman, I know

that marriage aside, whatever, I want to be involved with one

woman for a long time. But I've gotta work out a few psychological

things beforehand. I've gotta learn to give more."

After graduating from Precopius Greek

Orthodox School in Hinsdale, Ben enrolled at Loras College in

Dubuque, Iowa. He stayed there for a year, transferred to Loyola

University in New Orleans, then to the University of the Americas

in Mexico City. Despite this hopping around he kept his credits

in order and received a Bachelor of Arts degree in International

Relations from the University of Illinois. A year or so of graduate

study followed at Loyola University in Chicago and the University

of the Americas before Murphy went to the Pasadena Playhouse in

California and completed a two-year course, garnering a second

B.A., this one in Theater Arts.

Somehow the Armed Services passed him

by. "Even at the height of the Vietnam war they never drafted

me," Ben says. "I expected it every day and dreaded

it, because my career was just starting. Now I'm too old. I'm

29.

"I would have gone, yes. Because

with my education I probably would have ended up in Europe instead

of in Vietnam. Basically I'm a pacifist. I don't believe in killing

and fighting. I think the whole thing is insane. I thought it

was insane back in 1963 when I was at the University of Illinois

and we were studying Asian problems. I was there working in the

library when I heard that President Kennedy had been killed. I

remember running outside and the way some of the kids were screaming,"

Ben's voiced trailed away and he was silent for a moment. "Human

nature being what it is, nations, governments and people have

to go through their follies," he said finally. "But

as far as I'm concerned, I'm just going to step aside and make

sure it doesn't roll over me and those I love. Because human beings

are going to do stupid things. Yet at the same time I admire and

respect the people who get out and get behind things. If they

didn't do it, where would we be? Personally my loyalties don't

end at the border line of my country. They go beyond to people.

There's another human being on the other side who is important

too. Most of the letters I get are from kids. 11-12-13-year-olds.

They usually sign with something like love and peace. It's

the whole scene."

As in Hollywood, the anti-star syndrome

is very much in vogue. Ben typifies current attitudes. He may

go a few steps beyond. He doesn't need or want what is generally

referred to as the "phoney-baloney," the super car,

the clothes, the private clubs. He owns a vintage Chevrolet, the

kind automobile dealers refer to as a "good transportation

car." "And I wouldn't have that," he smiles, "if

it wasn't for my mother. She bought it for me."

Ben lives in a modest apartment near the

studio. It would take a fast five minutes for him to pack everything

he owns into a battered, brown leather suitcase. He's making pretty

good money and saving it. He's socking it away in land investments.

He'd like to go to Europe one day, headquarter in Paris and study

French. He'd like to put a pack on his back and trek from country

to country, much as he once criss-crossed the United States.

In order

to support himself when he was college-hopping, Ben worked at

a number of jobs. He sold shoes, dug ditches, painted houses,

drove a truck. He was once secretary to a priest. How did he come

by this position? "It was on the board at school," he

says nonchalantly.

In order

to support himself when he was college-hopping, Ben worked at

a number of jobs. He sold shoes, dug ditches, painted houses,

drove a truck. He was once secretary to a priest. How did he come

by this position? "It was on the board at school," he

says nonchalantly.

It was while he was at the University

in Mexico that Ben fell in love for the first time. He doesn't

elaborate on the affair, except to admit that it hurt when it

was over. "What a place to fall in love," he says. "We

used to get in my car and go all over the country staying in small

towns. She was an English girl. I never did learn how to speak

Spanish."

Ben would like to think about settling

down with one woman when he's about 35. If by that time

he has enough money. "I'm not going to get married until

I can support a wife and children the way I want," he says.

"And that means they won't have to struggle along with me.

I want to be able to give them everything. I want us to be able

to pick up and leave on the spur of the moment.

"I hope you realize," Ben smiled,

"that I'm over-talking all this stuff, because I'm trying

to answer you honestly and fully. These things I'm talking about

aren't big problems at all. I'm not sick by any means. None of

this hurts my life. It's just that I'm aware of every nuance of

my feelings. Most people are not aware of themselves; I am. I

have that facility of being able to walk into a room and I know

what's going on and what people think of me, what people think

of one another. It's that sort of thing. It's not because I'm

psychic. It's intuitive."

Ben approaches everything with a driving

determination to succeed. He either goes all the way or not at

all.

"When I learned to ski," he

says, "that's all I did for months. I skied. When something

interests me that's all I want to do until I've learned to do

it as well as I can. Then I'm bored and want to go on to something

else."

Acting, he insists, is not a passing fancy,

"I wouldn't give it up," he says. "Sometimes I

think about it. Sometimes in the heat of the day when there are

a million questions, I think I just gotta get out of here;

I gotta cut out. But I'm not going to. I've got a good thing

and I know it."

Ben grew impatient when the question of

sexploitation in films came up. "I don't know what sexploitation

means," he said. "I only see films I like or I don't

like. Do you see the subtle point I'm trying to make? It's unimportant.

A film is either artistically something I enjoy or I don't enjoy.

How they do it is not relevant. Those are values which are just

not important to me at all. That's the way it is with most of

my generation and the younger kids. Nudity is not important. As

an actor I would do anything I want to do. Would I do nudity?

I would if I thought it was necessary. But it's totally unimportant."

He looked up and flashed a broad grin.

The anger passed from his face. What had he said? "My emotions

go the full range every day." At this instant he looked comparatively

content.

"I am content," he allowed.

"Next week I'm leaving for Utah to go skiing. I've got a

couple of chicks I may or may not take along. The show is going

well and I love it. I've got no complaints."

Later, just before he said goodbye, he

got off on the subject of tennis. "Do you know of a tennis

ranch around here anywhere?" he asked. "I've heard of

them, a place where you lead a spartan life and just play tennis

every day, day in and day out. It's like a training camp. That's

what I'd really like to do when I get back from Utah. I've got

a couple of months before the series starts up again. Either that

or I'd like to head down to Mexico. There's a large part of Baja

I haven't seen. Yeah..."

With that he was off, an itchy foot against

the accelerator of a beat down car. Benjamin Murphy, a fascinating

highwayman if ever there was one.

Back

to Articles List

"Image?"

said Ben Murphy. "I'm probably going to come off as a swinger,

a guy who digs broads; the whole bit." He pushed his Eggs

Benedict, forked up a mouthful and chased it with a hungry pull

on a bottle of beer. Murphy, alias Jed "Kid" Curry

of Alias Smith and Jones was lunching in the Universal

commissary and discussing the vagaries of the acting profession.

"Of course, right now," he allowed, "I don't have

an image. But if the show holds I suppose they'll nail one on

me. I probably won't like it." But he'll go along with it

anyway.

"Image?"

said Ben Murphy. "I'm probably going to come off as a swinger,

a guy who digs broads; the whole bit." He pushed his Eggs

Benedict, forked up a mouthful and chased it with a hungry pull

on a bottle of beer. Murphy, alias Jed "Kid" Curry

of Alias Smith and Jones was lunching in the Universal

commissary and discussing the vagaries of the acting profession.

"Of course, right now," he allowed, "I don't have

an image. But if the show holds I suppose they'll nail one on

me. I probably won't like it." But he'll go along with it

anyway.

In order

to support himself when he was college-hopping, Ben worked at

a number of jobs. He sold shoes, dug ditches, painted houses,

drove a truck. He was once secretary to a priest. How did he come

by this position? "It was on the board at school," he

says nonchalantly.

In order

to support himself when he was college-hopping, Ben worked at

a number of jobs. He sold shoes, dug ditches, painted houses,

drove a truck. He was once secretary to a priest. How did he come

by this position? "It was on the board at school," he

says nonchalantly.