- Excerpt

from RIDING THE VIDEO RANGE, THE RISE AND FALL OF THE WESTERN

ON TELEVISION

- by Gary A. Yoggy

- McFarland & Company, Inc.: Jefferson,

North Carolina, and London, 1995

- pp. 471-484

Unlike The Guns of Will Sonnett, which

used a rhyming verse to explain the series premise at the beginning

of each show, Alias Smith and Jones employed a montage

of scenes from the two hour pilot plus a voice-over narrative

to open each episode:

Hannibal Heyes and Kid Curry, the two

most successful outlaws in the history of the West, and in all

the trains and banks they robbed, they never shot anyone. This

made our two latter-day Robin Hoods very popular--with everyone

but the railroads and the banks.

(Heyes and Curry are

shown being chased by a posse)

KID: There's one thing we gotta get,

Heyes.

HEYES: What's that?

KID: Outta this business!

(Heyes and Curry are

shown listening to)

SHERIFF TOM [sic] TREVORS: The Governor

can't come flat out and give you amnesty now. First, ya gotta

prove ya deserve it!

HEYES: So all we've gotta do is stay

outta trouble until the governor figures we deserve amnesty.

CURRY: But, in the meantime we'll still

be wanted?

SHERIFF: Well, that s true. Till then,

only you, me, and the governor'll know about it. It'll be our

secret.

HEYES: That's a good deal?

(Another shot of Hayes

[sic] and Curry being chased by a posse is shown)

HEYES: I sure wish the governor'd let

a few more people in on our secret.

The series, created by Glen A. Larson

and produced by Roy Huggins, was obviously inspired by the popular

1969 film Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, which starred

Paul Newman and Robert Redford. The movie romanticized the lives

of two actual bandits who robbed trains and banks at the turn

of the century. Directed by George Roy Hill from a screenplay

by William Goldman, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid

did well at the box office and with critics. Newsweek's

Paul D. Zimmerman wrote:

The Western, that Hollywood archetype,

has outlived its usefulness as a straight dramatic device in

which good, dressed in white, guns down evil, dressed in black.

Instead Goldman and Hill have turned out an anti Western... (in

which) the railroads are the villainous symbols of an increasingly

impersonal, industrialized and mercantile society.... The century

and frontier life are both ending, but Butch Cassidy and the

Sundance Kid refuse to surrender to this changing America, holding

up trains and banks as though the sheriff and the local posse

were their only adversaries.[24]

Years later noted film critic Leonard

Maltin gave the film four stars and described it as a "delightful

seriocomic character study masquerading as a Western."[25]

Alias Smith and Jones emphasizes the lighthearted comic

side of its two main characters, Kid Curry and Hannibal Heyes

(alias Thaddeus Jones and Joshua Smith), but can hardly be considered

an "anti-Western." Heyes and Curry are depicted as two

charming and courageous outlaws (formerly of the Devil's Hole

Gang) trying to go straight. There is a considerable price on

the head of each man ($10,000 "dead or alive") and practically

every marshal, sheriff and bounty hunter they run into would like

to collect that reward.

Like Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid,

who really existed, Kid Curry was based on an actual historical

character. (There is no record of a "Hannibal Heyes.")

The real "Kid," however, bore little resemblance to

the television version. Born Harvey Logan in Dodson, Missouri,

in 1865, he was the eldest of four boys who were orphaned in the

early seventies and sent to live with an aunt. At the age of 19,

Harvey set out with two of his younger brothers who planned on

becoming cowboys. They fell in with a gang of rustlers in Wyoming,

however. The leader of the gang was an ugly man with a distinctive

swagger and an even more distinctive name--Big Nose George Curry.

Harvey was fascinated by the man and from then on adopted the

name Kid Curry.

In appearance, the Kid was much shorter

than the actor who played him on television (Ben Murphy). He stood

five foot, seven and a half and weighed 150 pounds. His eyes were

dark brown and a heavy, "ratty looking" moustache grew

under his prominent nose. Despite his appearance, the Kid was

reputed to have had a fair share of success with women, perhaps

because he was polite and always acted like a gentleman. In fact

it was because of a girl, a pretty young miner's daughter called

Elfie, that Kid Curry shot and killed his first man--Pike Landusky,

her stepfather. Fifty-five year old Landusky had long been critical

of the Kid's association with his step-daughter, and there was

a terrible tension every time the two men came near each other.

Finally Curry found Landuskey half drunk in a bar and goaded him

into going for his gun, whereupon the Kid shot him down. He would

kill at least seven more men before his own death.

Joining up with Butch Cassidy and the

Wild Bunch, Curry participated in several train robberies as well

as a prison break. Whereas Butch Cassidy was a genuinely likable

man, Kid Curry was not. He was cold and ruthless, spoke little

and drank a lot. By the autumn of 1901, with train robbing played

out and with Butch and the Sundance Kid about to leave for South

America, Kid Curry was one of the West's most hunted men. He had

killed two lawmen and two cowboys the year before, and with bounty

hunters, Pinkerton Agents and sheriffs following his trail of

stolen bank notes he became even more vicious.

The Kid tried to reach Butch Cassidy in

South America, but the heat was on and he fled across the West

from Montana to Colorado. He shaved off his moustache and formed

his own gang. After robbing a train on July 7, 1903, a huge posse

cornered the Kid and his gang in a small canyon. There, he was

wounded, and before the law could reach him, he shot himself in

the temple. Drawn, haggard, in ragged clothes and a battered hat,

nobody recognized him as Kid Curry. In fact Lowell Spence, a Pinkerton

Agent who had been hunting the Kid, had to go to Colorado and

dig up the body before an official identification could be made.

Kid Curry's life had been a far cry from that of the amiable and

gallant hero of television's Alias Smith and Jones.

Ben

Murphy, who played television's Kid Curry, was born Benjamin Edward

Murphy, in Jonesboro, Arkansas. However, his father, who ran a

wholesale business, moved twice while Ben was still young and

he did his growing up in Memphis and Chicago. Working summers

driving a pie truck in Chicago, he earned $150 a week toward his

college expenses. It was a hard and dangerous job--drivers frequently

got mugged during the 60 stop route and Ben's supervisor dropped

dead of a heart attack, but Ben persevered.[26]

Ben

Murphy, who played television's Kid Curry, was born Benjamin Edward

Murphy, in Jonesboro, Arkansas. However, his father, who ran a

wholesale business, moved twice while Ben was still young and

he did his growing up in Memphis and Chicago. Working summers

driving a pie truck in Chicago, he earned $150 a week toward his

college expenses. It was a hard and dangerous job--drivers frequently

got mugged during the 60 stop route and Ben's supervisor dropped

dead of a heart attack, but Ben persevered.[26]

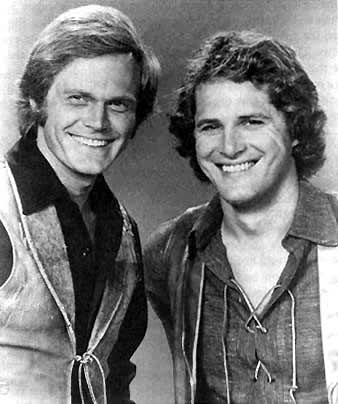

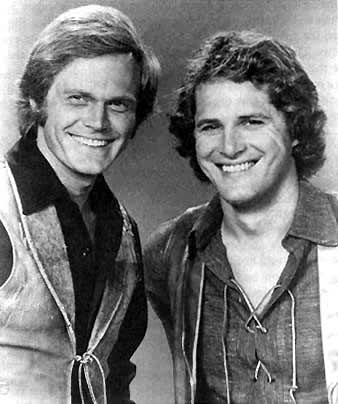

Photo Caption:

Peter Deuel (left; later simplified to Duel) as Hannibal Heyes

and Ben Murphy as Jed "Kid" Curry starred in the original

version of Alias Smith and Jones.

Murphy's first theatrical experience came

as a spear carrier in a University of Illinois production of Shakespeare's

Julius Caesar and he later played the "Young Man"

in Edward Albee's The American Dream. Then he left college

and drove to California. There, while appearing at the Pasadena

Playhouse in Life with Father, Murphy was "discovered"

and signed by agent Jack Donaldson. This led to a one-line role

in the Mike Nichols film, The Graduate (1967), where Ben

uttered the words, "Save me a piece" (of wedding cake).

He was paid $125 for one day's work and had to borrow money from

his mother to pay his Screen Actors Guild dues. Murphy was, however,

soon signed to a contract by Universal Studios and began appearing

in episodes of several of their television series, including The

Virginian, It Takes a Thief, and a couple of their

made-for-television movies. On The Name of the Game (1968—1971)

he was given the part of a young reporter named Joe Sample and

appeared intermittently for three seasons. Then at an NBC cocktail

party, a producer apologized for not using Ben more often on the

show. "That's all right," Murphy replied. "I'm

using my free time to look for film jobs"--and he was promptly

fired.[27] As Kid Curry on Alias Smith and Jones, Murphy

was often compared to Paul Newman in the Butch Cassidy film. When

reporters suggested that was why he got the role, he would bristle.

Series creator Larson and executive producer Huggins were both

impressed with Murphy. Huggins said in an interview with TV

Guide:

He's beautifully willing not to be the

typical Western hero. He s even willing to be the butt of the

jokes. [But the role] is better played straight than silly and

sometimes Ben goes too broad.[28]

Peter Deuel was cast as Kid Curry's pal

Hannibal Heyes. A loner who liked to walk in the woods while growing

up in Penfield, a small one-stoplight farming community outside

of Rochester, New York, Deuel was the son of the town's general

practitioner and nurse. Pete was interested in acting as early

as kindergarten, but did not contemplate a professional career

until he was in college. He was a poor student at St. Lawrence

University, but when his father saw him in the school production

of The Rose Tattoo, he told Pete, "If you want to

go to school, why don't you go to drama school instead of wasting

my money here?"[28]

Pete was accepted into the American Theater

Wing school in New York City and buckled down to serious study.

After graduation he appeared in a Family Service Society play

about syphilis. Then he earned his Equity card as a member of

a Shakespearean company and appeared in his first film, Wounded

in Action. This was followed by a stint as Tom Ewell's understudy

in the road company of Take Her, She's Mine. When the show

reached Los Angeles, Deuel decided to try his luck in a television

series and then to return to Broadway after five years. His plan

worked well, with Pete landing the role of John Cooper, Sally

Field's brother-in-law on Gidget (1965-1966), after guest

spots on such popular shows as Combat, Twelve O'Clock

High, The Fugitive and The Big Valley. At the

end of the five years, however, Deuel was offered the lead in

the well-received, though short-lived, situation comedy Love

on a Rooftop (1966-1967) as the newly married struggling apprentice

architect David Willis, opposite Judy Carne (who would later become

famous on Laugh-In). Deuel later explained why he dropped

his personal five year plan to accept the role:

... It was a fine series. It was sentimental

without being maudlin, although every once in a while it got

a bit sticky. I don't usually like to watch gooey sentimentality

myself, but sometimes it's a release. It allows you to sit and

cry, and you may be crying for a lot of other things.[30]

When Love on a Rooftop was canceled

after only one season, Deuel turned to films. He appeared in the

two hour pilot of Robert Young s hit series Marcus Welby, MD

(1969) and with Walter Brennan as a footloose young gambler named

Honest John Smith who was searching for the owner of a mysterious

fortune (shades of his role in Alias Smith and Jones right

down to the character's last name) in the made-for-television

film The Young Country (1970). He also was given his first

major big screen film role as pregnant Kim Darby's husband in

Generation (1969). Deuel's most satisfying and stimulating

roles came as a junkie in the pilot episode of Universal's The

Psychiatrist ("God Bless the Children") in 1970

and as a patient who desperately needs a kidney in The Interns

("The Price of Life"), also in 1970. Deuel claimed that

"these roles made everything else seem dull by comparison."[31]

Despite Deuel's preference for serious parts, he seemed comfortable

as the wide-eyed safecracker Hannibal Heyes, trying to go straight

in the dying days of the Old West in the comedy-adventure series,

Alias Smith and Jones:

I was footloose and fancy free at Universal

before this came along. Still, if I have to make a TV series

I prefer being in the great outdoors and around horses than playing

a lawyer, say, in a courtroom.[32]

However, comparisons that the press made

with Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid annoyed Deuel:

I frankly resented the constant needling

by the press every time I did an interview. It was always the

first question asked, and in my opinion a moot point.[33]

What made the interviews even more difficult

for Deuel (and Murphy, as well), was the fact that Universal wanted

to divorce the series from the movie. They tried to play down

the similarity which, Deuel claimed, began and ended with the

fact that "it was no longer profitable for two guys to continue

as outlaws." Deuel later mused,

It would be funny if the series runs

a couple of years, then the film is rereleased, and the new audience

that hasn't seen the movie will say "Butch Cassidy and the

Sundance Kid" resembles "Alias Smith and Jones."[34]

Alias Smith and Jones debuted with a two hour film on January 5, 1971.

Written and produced by former singer Glen A. Larson (who would

later produce such hit series as Switch, 1975-1978; B.J.

and the Bear, 1979-1981; and The Fall Guy, 1981-1986),

the pilot film laid the plot groundwork for the series. As the

opening narration (written by Glen Larson and Matthew Howard)

explains:

Nobody can really pinpoint just when

that period called the West ended. Maybe it was when the last

outlaws were captured or put out of business. If so, this story

is about the end of the West.

This was America's frontier at the turn

of the century... indoor plumbing and telephones, automobiles

and nickelodeons.

The West was getting to be downright

comfortable for everyone. Well, everyone but outlaws....

(Shot of Heyes and Curry riding hard.)

These two gentleman had gained great

notoriety for their crusade to keep the banks of the West open

around the clock. They were terribly successful. Something had

to be done... the days of the outlaw were numbered. But they

hadn't given up yet.

Hannibal Heyes and Jed "Kid"

Curry, a pair of notorious outlaws, are offered amnesty by the

governor of Wyoming Territory if they will bring in a vicious

desperado and his gang. They later discover, however, that their

amnesty (offered through a lawman friend, Sheriff Tom Trevors)

has several other strings attached. They must change their names

and stay out of trouble for a year (with only Trevors and the

governor aware of the agreement). As the concluding narration

explains:

So... for the following year, the West's

two most-wanted men would lead model lives... lives of temperance-moderation-and

tranquility. Hannibal Heyes and Kid Curry would cease to exist.

In their places would ride two men of

peace.... Alias Smith and Jones.

In addition to Deuel and Murphy the film

featured former Virginian James Drury as Trevors, F-Troop

alumnus Forrest Tucker as a deputy, Susan Saint James as the romantic

interest, and veteran Western performers Jeanette Nolan, Earl

Holliman and John Russell in supporting roles.

On January 21, 1971, the weekly hour-long

version premiered with an episode entitled "The McCreedy

Bust." The show, which drew a respectable viewing audience,

relates the efforts of Smith and Jones to recover a bust of Julius

Caesar stolen from a wealthy rancher (McCreedy) by a Mexican grandee.

The pair are successful and paid a $10,000 fee, only to lose it

back to McCreedy in a clever poker ruse. It seems that according

to Hoyle, a straight does not beat two of a kind in draw poker

unless specifically agreed to by the players in advance. (Hoyle's

Book of Games was usually followed in the latter part of the

nineteenth century. This ploy had been used years earlier on Maverick

when Samantha Crawford used a pair of nines to beat Bret's straight

in "According to Hoyle.")

The duo do ultimately get the last laugh,

however. Heyes (alias Smith), an expert poker player, bets McCreedy

$20,000 that he can take any 25 cards dealt to him at random and

make five pat poker hands out of them. After he wins the bet,

he explains to McCreedy that it works nine out of every ten times.

Then, to add insult to injury, the Mexican grandee and his men

show up and steal all the money as well as the bust of Caesar.

Burl Ives was delightfully robust as McCreedy, Cesar Romero was

fine as the Mexican grandee, and Edward Andrews turned in a typically

solid performance as a bemused banker friend of McCreedy's. Most

critics applauded the show. Respected critic Ben Gross of the

New York Daily News (January 22, 1971) wrote:

A rarity came to TV last night... a new

Western series, "Alias Smith and Jones," over ABC....

As oatburners go, it's a pretty good one, certain to please the

aficionados and--who knows?--because it is invested with a light

touch and a sense of humor, it may even snare a sophisticate

or two....

The new show... has all the expected

conventional elements: the raw frontier town, the lawmen and

the outlaws, the gamblers, the stage coach, the saloon with its

garish girls, etc. etc. In other words, present are all of the

atmosphere, the settings and the props that one associates with

this escapist form of entertainment....

... Pete Duel and Ben Murphy give picturesque

performances as the two former badmen now trying to go straight....

What I especially liked about the opening installment was its

vein of comedy buried beneath the obvious melodrama of the action.

Tom Mackin of the Newark, New Jersey,

Evening News (January 22, 1971) echoed Gross' sentiments:

There was a lot to like about "Alias

Smith and Jones" the light-hearted western brought in by

ABC last night. It teetered precariously on slapstick throughout

the hour, but it managed to stay honest, retain its sense of

humor and even come up with a new plot twist or two.

... It was a droll, fast-moving episode,

well acted by a particularly adept cast.

Cleveland Amory was not as lavish with

his praise in TV Guide, but did have to admit he liked

the show in his March 6, 1971, review:

One thing you'll have to grant this show.

It doesn't promise very much... but it's got a terrific premise....

Another thing you'll have to grant is

that the two principals are fine actors.... [The show] also has

a plethora of guest stars....

... But that is about all we can say.

At the beginning of the third season,

Variety (September 20, 1972) was still singing the show's

praises:

The operative word for "Smith and

Jones" is amiable. While they usually carry guns, they rarely

fire them. ... While their frontier world is largely populated

by the usual assortment of toughs and macho types, the whole

thing is played for laughs.

Between the first episode of January 1971,

and episode number 38, which marked the opening of the series'

third season, however, tragedy had befallen the show. Pete Duel

(he had changed the spelling for simplicity) had embarked upon

a television career with high expectations. The longer he remained

in Hollywood, however, the more frustrated he became. He thought

most of the scripts he was required to do were garbage and he

had developed a reputation for fighting with directors. Duel had

attempted to change the system by running for office in the Screen

Actors Guild, but lost. As biographer Tim Brooks explains:

Usually clad in jeans, [Duel] was a political

activist working for McCarthy in '68 and caring about ecology--he

was a true child of the '60s. Thousands of young hopefuls would

have given their eyeteeth for his success, but Duel always wanted

more, both as an actor and as a person.[35]

Still, Duel's apparent suicide came as

a shock. It was New Year's Eve, 1971. He had been filming an episode

of Alias Smith and Jones earlier in the day. That evening

he read the script for the next show and watched a completed episode

of the series. Duel was with his girlfriend, who later said nothing

seemed wrong, although he had been drinking and said that he hated

the show he had watched. Late that night, she heard a gunshot

from the next room, and ran to find him sprawled on the floor.

Despite all the evidence to the contrary, many friends, as well

as fans, felt that it must have been a terrible accident--or murder.

Police ruled Duel's death a "probable suicide" and closed

the case. It was an ending unlike any ever contemplated for the

popular lighthearted series of which he was a star.

With four more episodes needed to complete

the season, the role of Joshua Smith had to be quickly recast.

Roger Davis, who had been doing the show's opening and closing

narration, was chosen, and a partially completed episode, "The

Biggest Game in the West," was finished with Davis redoing

scenes that had already been filmed by Duel. No explanation was

made in the storyline, with Davis taking over the role as if he

had been playing it for the entire run of the show (in much the

same way that Dick Sargent had taken over for Dick York in Bewitched

in 1969).

Davis, a native of Louisville, Kentucky,

made his television acting debut in 1962 as Private Roger Gibson,

a callow young driver, on ABC's World War II drama The Gallant

Men. Later he appeared in ABC's daytime serial Dark Shadows

as Peter Bradford (Maggie's love interest when she is transported

to the past). The opportunity for his involvement with Alias

Smith and Jones undoubtedly dates to his selection as the

amiable conman Stephen Foster Moody, in The Young Country.

That 1970 made-for-television film was written, directed and produced

by Alias Smith and Jones producer Roy Huggins. Aaron Spelling

also used Davis in the 1971 beach-bum "buddy" picture

River of Gold (with Guns of Will Sonnett's Dack

Rambo).

In addition to his work as narrator, Huggins

also gave Davis a guest-starring role as the title villain in

an earlier episode of Alias Smith and Jones called "Smiler

with a Gun." During that episode, Davis, as gambler, con-artist

and ladies man Danny Billson, teams up with Duel and Murphy to

help an old prospector (Will Geer) mine gold. The night before

they are set to return to civilization with the fruits of their

joint labor, Billson sneaks off with the gold and leaves the other

three with no horses and little water.

Photo

Caption: Roger Davis (left)and

Ben Murphy finish the series as Alias Smith and Jones,

from 1972 on.

Photo

Caption: Roger Davis (left)and

Ben Murphy finish the series as Alias Smith and Jones,

from 1972 on.

The Kid and Heyes survive the trek across

the desert, but the old prospector dies and the two vow revenge

on their former crony. They finally find Billson running a saloon.

After refusing to turn over the proceeds from the sale of the

gold to Heyes and Curry, Billson goads Curry into a showdown gunfight.

In front of the town sheriff's eyes, Curry is forced to kill Billson

in self-defense. (This is one of the few instances in the 49 episode

series that Curry, who usually has his gun out and leveled before

his opponent can even clear his holster, actually kills anyone.)

The repartee among the three worked well, especially during the

first half of the story when all are pals. This, as well as Davis'

physical stature and easy-going manner, obviously impressed Huggins.

Perennial television game show host Ralph Story replaced Davis

as narrator and several new segments were filmed for the opening

montage showing Davis as Hannibal Heyes.

The quality of the series did not suffer

noticeably when Davis took over for Duel, but this was as much

the result of good scripts and supporting casts as it was the

efforts of its two stars. The series bore the indelible mark of

executive producer Huggins, who wrote most of the stories under

the pseudonym John Thomas James. Huggins, who was one of the creators

of Maverick in 1957 and would serve as producer and occasional

writer for the first three seasons, loved clever stories about

con games, poker, gambling, switches, land swindles and frauds,

horse racing and the like, incorporated such plot devices into

many of the episodes of Alias Smith and Jones. "The

McCreedy Bust," "Exit from Wickenberg," "The

Night of the Red Dog (in which a variation on poker called Montana

Red Dog plays a significant role in the story), "The Men

That Corrupted Hadleyburg," "The Biggest Game in the

West," "Which Way to the O.K. Corral?" "Don't

Get Mad, Get Even," and "What's in It for Mia?"

all feature poker or some other card game like blackjack. (Heyes

had a real knack for exposing cheating of all kinds--especially

marked cards.) Jewel switches are central to the plots of "A

Fistful of Diamonds" and "Never Trust an Honest Man,"

and money is cleverly switched in "Jailbreak at Junction

City," "The Men Who Broke the Bank at Red Gap,"

"Don't Get Mad, Get Even," "The Girl in Boxcar

Number Three," and "What's in It for Mia?" while

gambling on horse races is essential to the story of "The

Great Shell Game." A land swindle is employed in "Dreadful

Sorry, Clementine" and "The Root of It All" concerns

a search for buried treasure.

Huggins, who was also involved in the

production of such hit series as The Fugitive (1963-1967),

Run for Your Life (1965-1968) and The Lawyers segments

of The Bold Ones (1969-1972) and would later produce Jim

Garner's television series The Rockford Files (1974-1980),

especially favored stories where a crook was beaten at his own

game. Notable among episodes with such a theme were "Dreadful

Sorry, Clementine," "The Wrong Train to Brimstone,"

"The Great Shell Game," "A Fistful of Diamonds,"

"The Man Who Broke the Bank at Red Gap," "The Men

That Corrupted Hadleyburg," "Which Way to the O.K. Corral?"

"Don't Get Mad, Get Even)" and "What's in It for

Mia?"

Photo Caption: Walter

Brennan (left), in another of his patented character roles, appeared

with Murphy (center) and Deuel in several episodes of Alias

Smith and Jones.

Photo Caption: Walter

Brennan (left), in another of his patented character roles, appeared

with Murphy (center) and Deuel in several episodes of Alias

Smith and Jones.

Another Maverick-type Huggins touch

was the inclusion of likable and interesting con-artists who would

be used in several episodes. Among such characters were Silky

O'Sullivan, a lovable retired con-artist (a tour de force for

Walter Brennan), in "The Day They Hanged Kid Curry"

(in which Brennan also appears in drag as Curry's grandmother),

"Twenty-One Days to Tenstrike" and "Don't Get Mad,

Get Even"; "Mac" McCreedy, a cagey, stingy rancher

(Burl Ives at his droll best), in "The McCreedy Bust,"

"The McCreedy Bust--Going, Going, Gone" and "The

McCreedy Feud" (each episode also featured Cesar Romero as

Señor Alvarez, a charming and crafty Mexican grandee--each

episode being a continuation of the earlier stories); "Soapy"

Sylvester, a distinguished and suave former confidence man, much

like Silky Sullivan only considerably more polished (a witty role

for Ben Casey alumnus, Sam Jaffe), in "The Great Shell Game"

and "A Fistful of Diamonds"; Winfield Fletcher, a tightfisted,

seedy, scheming banker (a superb characterization by Rudy Vallee),

in "Dreadful Sorry, Clementine" and "The Man Who

Broke the Bank at Red Gap"; and the persistent, obnoxious

and slightly dishonest detective Harry Briscol of the Bannerman

Detective Agency (J.D. Cannon giving a slick and professional

performance), in "The Wrong Train to Brimstone," "The

Legacy of Charlie O'Rourke," "The Reformation of Harry

Briscol" (in which Briscol actually steals $50,000 but is

convinced by Heyes and Curry to return it) and "The Long

Chase."

Women con-artists were plentiful too--a

la Samantha Crawford, Melanie Blake, and Modesty Blame of Maverick.

The best remembered is Clementine Hale (a delightful portrayal

by future Emmy and Academy Award winning actress, Sally Field,

fresh from three years as television's Flying Nun), although

she appeared in only two episodes, "Dreadful Sorry, Clementine"

and "The Clementine Incident." (Clementine had the only

photo in existence of Curry and Heyes and used it to get them

to help her with various schemes.) Appearing more often was Georgette

"George" Sinclaire, another beautiful schemer who doubled

occasionally as a saloon singer (a showcase for the multitalented

Michele Lee), in "Which Way to the O.K. Corral?," "Don't

Get Mad, Get Even," and "Bad Night in Big Butte."

Another recurring character was the Mexican

bandit El Clavo, who was featured in two episodes, "Journey

from San Juan" and "Miracle at Santa Marta." Nico

Minardos was cast as the bandito in the first El Clavo episode,

which set off a controversy involving "reverse discrimination"

in the entertainment world that was to have consequences far beyond

the series itself. The ethnic minorities advocacy group Justicia

voiced their strong objections to ABC regarding their selection

of Minardos, stating that a Mexican American should have been

cast in the role. The company, however, stood its ground and Minardos

played the role. The series' producers felt the episode was so

well done and the character of El Clavo so interesting that a

sequel was written for the following season. They intended to

have Minardos repeat his role.

However, the producers were notified by

ABC that they preferred that the casting be revised, and, in compliance

with this request, Minardos was dropped from consideration and

another actor, one of Latin origin, was engaged for the role originally

intended for Minardos. Minardos complained to both ABC and the

Screen Actors Guild. The associate national executive secretary

of SAG wrote a strongly worded letter to ABC executives objecting

to their treatment of Minardos and charging them with reverse

discrimination. The landmark statement read in part:

It is a vital principle involving actors

which concerns us--that is the right of all actors to compete

and play roles for which they have the training, background and

experience. The essence of minority hiring lies within that statement

also. All actors should have the right to compete for roles.

If the premise is not correct, minority groups of actors are

doomed to portray only their ethnic minority roles....

The concept that Italians play Italians,

Mexicans play Mexicans, Greeks play Greeks and they all play

nothing else is not what "fair employment"; was intended

to achieve. The inconsistency of such a hiring practice with

both the goals of fair employment and the essence of the actor's

craft is painfully clear.[36]

What the Guild was saying was that under

such a narrow interpretation of minority rights, Yul Brynner could

not have portrayed the King of Siam nor Anthony Quinn, Zorba.

It was wrong, in effect, to penalize one minority to help another.

The ultimate result was that Minardos was reinstated in the role,

a precedent was established and viewers were treated to another

entertaining episode of Alias Smith and Jones.

Another recurring character was Sheriff

Tom Trevors who appeared in the two hour pilot, and in the episodes

"Shootout at Diablo Station," "The Day the Amnesty

Came Through," and "Witness to a Lynching." Lawman's

John Russell played Trevors in all of the episodes except "Shootout."

Inexplicably, Mike Road was Trevors in that episode, while Russell

appeared in a bit role as a deputy marshal in "Which Way

to the O.K. Corral?" Russell was perfect as the stern-faced

lawman who knew Smith and Jones' real identities as well as the

governor's conditional offer of amnesty. (Road also had prior

experience playing a lawman--as Marshal Tom Sellers in Buckskin.)

During their adventures, Joshua and Thaddeus

encounter more than their share of beautiful women. Some are vulnerable,

like Heather Menzies in "The Girl in Boxcar Number Three";

some are treacherous, like Diana Muldaur in "The Great Shell

Game"; some are greedy, like Judy Carne in "The Root

of It All"; some are motherly, like Vera Miles in "The

Posse That Wouldn't Quit"; some are ambitious, like Jane

Merrow in "The Reformation of Harry Briscoe"; some are

sexy, like Sheree North in "The Men That Corrupted Hadleyburg";

some are schemers, like Ida Lupino in "What's in It for Mia?";

some are pawns of men they love, like Shirley Knight in "The

Ten Days That Shook Kid Curry"; some are devoted to their

fathers, like Brenda Scott in "Witness to a Lynching";

some are dominated by an older brother, like Laurette Spang in

"Only Three to a Bed"; and some are husband hunters,

like Jo Ann Pflug in the same episode.

Three of the most interesting and diverse

women appear in "Six Strangers at Apache Springs": Carmen

Mathews plays a spunky widow who hires Smith and Jones to dig

up the gold she and her husband hid from marauding Indians; Patricia

Harty is the spoiled wife of an Indian agent who neither likes

the West nor appreciates her husband's courage and dedication

to duty; and Sian Barbara Allen portrays a quiet but devoted evangelist

who has been duped by a crooked gambler. The lives of each are

changed for the better by Smith and Jones.

In their attempts to "go straight,"

Curry and Heyes engage in a variety of occupations, although each

episode usually involves them in some sort of gambling or con

game. Some of their jobs are as mundane as prospecting for gold

in "Smiler with a Gun" and "The Night of the Red

Dog," herding cattle (or rounding up strays) in "The

Reformation of Harry Briscoe," "Journey from San Juan"

and "Bushwhack!" or capturing and breaking wild horses

in "Three to a Bed." On other occasions they engage

in more dangerous work, like transporting money for a lawyer in

"The Girl in Boxcar Number Three" and protecting two

government witnesses in "Witness to a Lynching." In

"Something to Get Hung About," they start out playing

Cupid and end up solving a murder and saving an innocent man from

the gallows. But Curry and Heyes always try to stay on the "right"

side of the law. As they explain to a would-be counterfeiter and

his daughter in "What's in It for Mia?":

CURRY: We try to avoid violence at all

times, not to mention anything illegal.

HEYES: Sometimes shady maybe, but never

illegal.

Another enjoyable feature of Alias

Smith and Jones is the use in many guest and supporting roles

of the stars of previously canceled television Westerns. It is

a real pleasure to see such veterans of the video range as Neville

Brand of Laredo (in "Shootout at Diablo Station"

and "Which Way to the O.K. Corral?"), Peter Breck of

Black Saddle and The Big Valley (in "The Great

Shell Game"), the aforementioned Walter Brennan, Pat Buttram

of The Gene Autry Show (in "Bad Night in Big Butte"),

Rory Calhoun of The Texan (in "The Night of the Red

Dog"), Rod Cameron of State Trooper (in "The

Biggest Game in the West" and "High Lonesome Country"),

David Canary of Bonanza (in "The Strange Fate of Conrad

Meyer Zulick"), Robert Colbert of Maverick (in "Twenty-One

Days to Tenstrike"), Jackie Coogan of Cowboy G-Men

(in "Which Way to the O.K. Corral?" "McGriffin"

and "Dreadful Sorry, Clementine"), Glenn Corbett of

The Road West (in "Twenty-One Days to Tenstrike"

and "Bushwhack!"), Andy Devine of Wild Bill Hickok

(in "The Men That Corrupted Hadleyburg"), James

Drury of The Virginian (in "The Long Chase"),

Buddy Ebsen of Davy Crockett and Northwest Passage

(in "What s in It for Mia?" and "High Lonesome

Country"), Jack Elam of The Dakotas and Temple

Houston (in "Bad Night in Big Butte"), Paul Fix

of The Rifleman (in "The Night of the Red Dog"

and "Only Three to a Bed"), Earl Holliman of Hotel

de Paree in ("The Day They Hanged Kid Curry"), Jack

Kelly of Maverick in ("The Night of the Red Dog"),

Lee Majors of The Big Valley (in "The McCreedy Bust--Going,

Going, Gone"), Cameron Mitchell of High Chaparral

(as Wyatt Earp in "Which Way to the O.K. Corral?"),

George Montgomery of Cimarron City (in "Jailbreak

at Junction City"), Slim Pickens of The Outlaws and

Custer (in "Exit from Wickenberg," "The Man

Who Murdered Himself," and "The Strange Fate of Conrad

Meyer Zulick"), Pernell Roberts of Bonanza (in "Exit

from Wickenberg" and "Twenty-One Days to Tenstrike"),

the aforementioned John Russell and William Smith of Laredo

(in "What Happened at the XST?") and Chill Wills

of The Rounders (in "The Biggest Game in the West").

Roy Huggins kept many otherwise unemployed

television actors and actresses busy. In addition to the Western

stars and others already mentioned there were Jack Albertson of

The Thin Man (in "Jailbreak at Junction City"),

Jim Backus of I Married Joan and Gilligan's Island

(in "The Biggest Game in the West"), John Banner of

Hogan's Heroes (in "Don't Get Mad, Get Even"), Joseph

Campanella of Mannix (in "The Fifth Victim"),

Judy Carne, Duel's former costar in Love on a Rooftop,

and Tom Ewell of The Tom Ewell Show (both in "The

Root of It All"), Jack Cassidy of He and She (in "How

to Rob a Bank in One Hard Lesson"), Wally Cox of Mr. Peepers

(in "The Men that Corrupted Hadleyburg"), Howard

Duff of Felony Squad (in "Shootout at Diablo Station"),

Joe Flynn of McHale's Navy (in "The Night of the Red

Dog"), Alan Hale of Gillian's Island (in "The

Girl in Boxcar Number Three"), Diana Hyland of Peyton

Place in "Return to Devil's Hole"), Dean Jagger

of Mr. Novak and John Kerr of Peyton Place (both

in "Only Three to a Bed"), Mark Lenard of Star Trek

(in "Exit from Wickenberg"), Patrick Macnee of The

Avengers and Juliet Mills of Nanny and the Professor (both

in "The Man Who Murdered Himself ), John McGiver of The

Patty Duke Show (in "Witness to a Lynching"), Robert

Morse of That's Life (in "The Day They Hanged Kid

Curry"), Diana Muldaur of McCloud (in "The Great

Shell Game"), Arthur O'Connell of Mr. Peepers (in

"Bad Night at Big Butte"), Ann Sothern of Private

Secretary and The Ann Sothern Show (in "Everything

Else You Can Steal"), Craig Stevens of Peter Gunn

(in "Miracle at Santa Marta"), William Windom of The

Farmer's Daughter (in "The Wrong Train to Brimstone"),

and Jane Wyatt of Father Knows Best (in "The Reformation

of Harry Briscoe"). All in all, Alias Smith and Jones

provided viewers with a veritable "who's who" in television

land.

An analysis of one of the more meaningful

and interesting adventures is in order. "The Bounty Hunter"

features guest star Louis Gossett as Joe Sims, "bounty hunter--professional."

Sims captures Curry and Heyes on the trail and though they try

to talk him out of it, he declares his intention of turning them

over to the nearest sheriff for the reward:

SIMS: Any description on any outlaw worth

more than two thousand dollars, I got locked up in my head down

to the last button on his shirt. And I don't just go by one description

on a man. I compare different ones, talk to people, ask questions.

Yeah, I'm workin' all the time. That's how I was able to spot

you two right off. ... I ain't got nothin' against you personally,

but like I said, I'm a bounty hunter--professional. But for twenty

thousand dollars for the two of you, gonna be the biggest score

I ever made...

HEYES: How'd you get in this line of

business, Joe?

SIMS: Well, I'll tell ya. Ain't much

a black man can do these days. Before the war, I was a slave.

Then, afterwards, I just drifted West and the further I went,

the further I got away from the way things used to be back home.

Sometimes, that's good. Sometimes, that's bad. Depends on the

kind of people you run into. Nobody pay a black man more'n room

and board and that's if he can get work. In the old days, if

ya got sick, why the master, he'd have to take care of ya. Now

days if you get sick, you just out of luck. That's why I became

a bounty hunter, for the money. Black man ain't gonna be out

of luck if he got money.

Curry and Heyes are able to escape when

a rattlesnake spooks Sims' horse. In the chase that follows, Sims

accidently shoots and kills the horse of a white cowboy and he

and his white cronies prepare to string Sims up. After saving

Sims' life, by chasing off the wouldbe lynchers with a volley

of gunfire, Curry and Heyes continue on their way, content that

they have done the right thing. Shortly thereafter, Sims ambushes

Curry and Heyes and again takes them prisoner. When questioned

about his lack of gratitude, Sims explains he did it for the money.

HEYES: Joe, I hate to say this but I

don't think you're showin' the proper gratitude.

SIMS: What's that?

CURRY: Don't you know why we did this?

SIMS: Tell ya the truth, that's what's

been puzzlin' me. Seems kinda stupid ta me.

HEYES: Stupid!?!

SIMS: Yeah sir! Don't know why ya wanna

save my skin, when ya could have saved your own skins instead,

especially since I'm dead set on taken ya in. Now, don't that

sound kind of stupid ta you?

A little farther along the trail, three

white drifters stop Sims and take his prisoners from him so that

they and not he can collect the reward. Meanwhile, Sims walks

to the nearest ranch, buys another horse and gun and is able to

recapture his prisoners along with two of the three men. The third

one, however, sneaks back to their camp that night and is about

to kill Sims. Curry, who has gotten loose from his ropes, shoots

the drifter and again saves Joe s life. Still, Joe is set on turning

Curry and Heyes in for the reward:

CURRY: You know what you are? You are

a miserable ingrate! You know that? He was gonna kill you. We

have now saved your life twice. Now, how can you do this ta us?

SIMS: Well, don't think it's so easy!

You're takin' all the pleasure I'm ever gonna get outta spendin'

that twenty thousand dollars. Every time I think of the way you

saved my life, ain't gonna be no fun spendin' that money, no

fun at all. In fact, I may just invest it instead.

Later, the story becomes more serious:

HEYES: Just tell me one thing. Why are

you so all fired ornery?

SIMS: Nothin' I can do about that. Some

black folks, ya know, figure they owe white folks a lotta harm

for all what they done. I don't feel that way. I don't feel I

owe 'em any harm. I don't feel I owe 'em anything else either.

I guess that's why I don't know nothin' 'bout gratitude. It been

taken outta me a long time ago.

HEYES: That's sad, Joe. That's a sad

way ta be.

SIMS: I guess...

Another group of whites come upon them.

Since their leader feels that it is not the place of a black man

to arrest white folks, he orders two of his men to take Curry

and Heyes into town to check their identities and shoots Sims

in the back as he rides away. Curry and Heyes escape, but arrive

too late to save Joe, who dies in their arms. They bury him, but

decide to report Joe's murder to the nearest sheriff, even at

the risk of their own safety. They had become fond of Joe and

feel it is the least that they can do for him now, although they

know in their hearts that, had he lived, Joe would have turned

them both in for the reward money. This excellent story by John

Thomas James (Huggins) contains both humor and tragedy. It is

both a comment on the plight of the black man at the end of the

Civil War and on his contemporary problems. It represents Alias

Smith and Jones at its best.

In the final episode, "Only Three

to a Bed," it appears that our two heroes are at last going

to find themselves wives and settle down. Alas, as in each of

the preceding 48 episodes, they escape the clutches of respectability

at the last minute. Still, they had managed, with great difficulty,

to trod the "straight and narrow" for nearly three seasons.

Smith and Jones deserved a better fate than cancellation before

their amnesty came through. The producers should resurrect this

fine series for a special television film (a la Gunsmoke) and

finally resolve this problem once and for all. (Of course, then

they would not be "Smith" and "Jones" anymore.)

One can heartily recommend this series in its syndicated reruns.

************************************************************

- 24. Quoted in Parrish and Pitts, Great

Weatern Pictures, p. 46.

- 25. Leonard Maltin, TV Movies and

Video Guide (1991 edition), p. 154.

- 26. Arnold Hano, "The World's Greatest

Love," TV Guide (February 19, 1972), p. 22.

- 27. Ibid.

- 28. Quoted in Ibid, p. 23.

- 29. Quoted in TV Guide (May 15,

1971), p. 30.

- 30. Quoted in Ibid.

- 31. Quoted in Kay Gardella, "Pete's

Not Convinced He's Lucky," Sunday News (April 25,

1971), p. S20.

- 32. Quoted in Ibid.

- 33. Quoted in Ibid.

- 34. Quoted in Ibid.

- 35. Brooks, Directory of TV Stars,

P. 244.

- 36. Quoted in Variety (August

16, 1972), p. 1, 40.

Back to Articles List

Ben

Murphy, who played television's Kid Curry, was born Benjamin Edward

Murphy, in Jonesboro, Arkansas. However, his father, who ran a

wholesale business, moved twice while Ben was still young and

he did his growing up in Memphis and Chicago. Working summers

driving a pie truck in Chicago, he earned $150 a week toward his

college expenses. It was a hard and dangerous job--drivers frequently

got mugged during the 60 stop route and Ben's supervisor dropped

dead of a heart attack, but Ben persevered.[26]

Ben

Murphy, who played television's Kid Curry, was born Benjamin Edward

Murphy, in Jonesboro, Arkansas. However, his father, who ran a

wholesale business, moved twice while Ben was still young and

he did his growing up in Memphis and Chicago. Working summers

driving a pie truck in Chicago, he earned $150 a week toward his

college expenses. It was a hard and dangerous job--drivers frequently

got mugged during the 60 stop route and Ben's supervisor dropped

dead of a heart attack, but Ben persevered.[26] Photo

Caption: Roger Davis (left)and

Ben Murphy finish the series as Alias Smith and Jones,

from 1972 on.

Photo

Caption: Roger Davis (left)and

Ben Murphy finish the series as Alias Smith and Jones,

from 1972 on. Photo Caption: Walter

Brennan (left), in another of his patented character roles, appeared

with Murphy (center) and Deuel in several episodes of Alias

Smith and Jones.

Photo Caption: Walter

Brennan (left), in another of his patented character roles, appeared

with Murphy (center) and Deuel in several episodes of Alias

Smith and Jones.