- PETER DUEL: HE CARED TOO MUCH TO LIVE...

- by Morris Townsend

- Silver Screen, April 1972

It was like a bizarre tableau from a horror movie.

There was a shot. Diane Ray sprang out of bed and ran to the

living room. Her terror-filled eves found nothing upright--except

the still standing Christmas tree. Then she saw Pete crumpled

at the foot of the tree where only a few days earlier they had

shared the pleasant laughter of opening presents and exclaiming

over them.

Christmas was nice, they had agreed. In

fact, that was why the tree was still there on December 31. Throwing

the tree out would be like turning a loved one out into the streets.

So they let it stay; let its cheerfulness warm them a bit longer,

and prolong the peace and joy and fellowship that the holiday

was supposed to represent.

Besides, this was not one of those Christmas

trees that would end in ashes or be carted away in a dump truck.

It was a living tree, nurtured in water in Pete's living room,

and it would be nurtured in the soil around his rustic two bedroom

home in the Beachwood Village section of Hollywood Hills. Peter

Duel was no cocktail party ecologist. He lived ecology, breathed

it, and practiced it.

Diane

screamed. A muffled, Oh-my-God, not-wanting-to-believe scream.

She faltered dizzily and the room began to swim. But somehow she

managed to reach the phone and call the police.

Diane

screamed. A muffled, Oh-my-God, not-wanting-to-believe scream.

She faltered dizzily and the room began to swim. But somehow she

managed to reach the phone and call the police.

It was almost 1:30 a.m., the last day

of 1971. And Peter Duel had chosen not to wait until midnight

to ring out the old year.

Or had he indeed chosen? A .38 calibre

revolver lay at his side. Had he meant to fire it or had if somehow

been an accident?

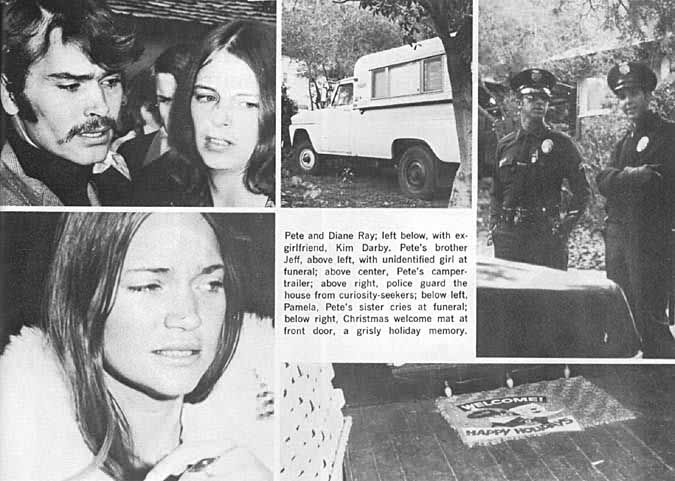

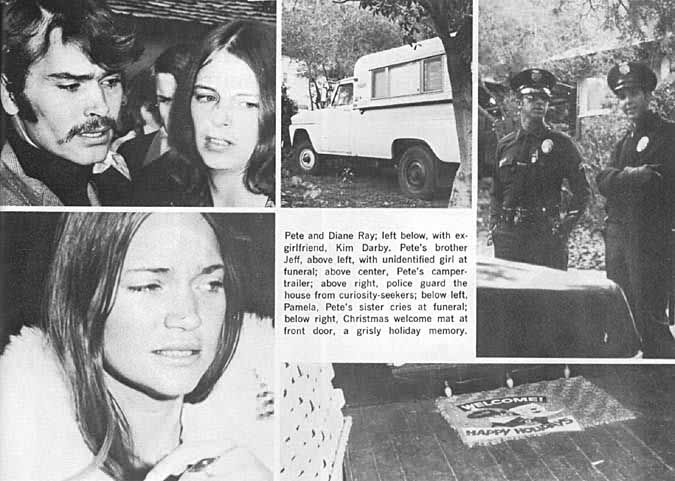

Had Peter Duel and Diane Ray been more

conventional, they would have married. But Diane grieved no less

than a widow would have, nor loved him less than a wife.

Pete, in retrospect, would surely have

married her, although neither of them thought about marriage as

anything but a superficial tribal rite that had long ago become

outdated.

They keep saying he died because he

drank too much.

He drank that night, and death was his nightcap.

Don't they know that Pete drank not because he didn't care about

life--but because he cared too much?

Services for Pete were held in the pastoral

surroundings of Self Realization Temple in Pacific Palisades.

One hundred and fifty friends and relatives

crowded into the small chapel. Almost a thousand were outside

as the services were funneled through an amplifying system.

A handful of the mourners were fairly

recognizable. Roy Thinnes. Joe Flynn. Fellow ecologist Henry Gibson.

Ben Murphy, Pete's co-star on "Alias Smith and Jones,"

had been at the mortuary earlier with Pete's parents, Dr. and

Mrs. Ellstorm Duel, but was too broken up to make it to the Temple.

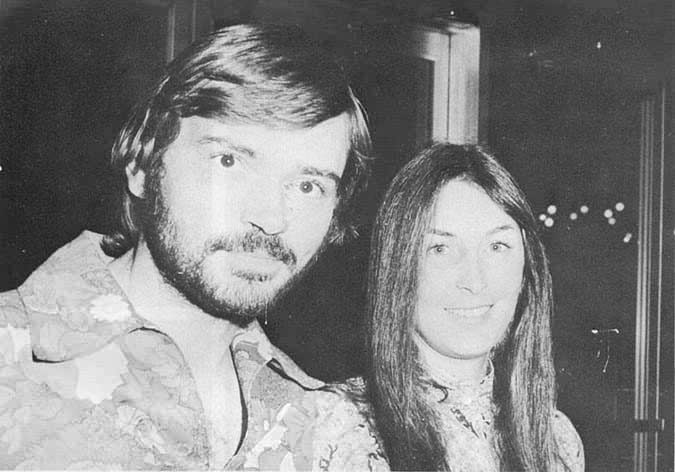

Diane Louise Ray, her natural brown hair

gathered in a severe bun on top of her head, no makeup on her

face (the way Pete had always liked it) stood and spoke as one

who had known Pete. She read a five line poem Peter had written,

called "Love."

Their common passion for a world of gentility

and justice had brought Diane and Peter together. Sometimes they

fought, but that was because their convictions came with strong

will. Once they had broken up, but they could not stay apart.

They had watched Pete's show on television

that fateful night and when it was over he switched on the Laker

basketball game. He drank a lot that evening, and it pained Diane

that he did. And it pained Pete--and he drank more to dull the

pain. That's how it always was--that Pete drank because he was

despondent, not the other way around. And that he was despondent

because he cared so much about everything, not because he didn't

care at all.

After a while Diane had dozed off. That

night, while Diane slept, Pete brooded and drank.

A rattling newspaper woke her. She blinked

and looked up, and saw Pete standing nude at the dresser, getting

something out of one of the drawers.

Peter, Peter, why are you so restless?

He finished peeling off the newspaper

and took out a .38 calibre revolver he kept there.

"I'll see you later," Pete said.

Diane rubbed sleep-lidded eyes. Was she

dreaming all this?

Then there was the shot, and she sat bolt

upright. That was not a dream.

She ran to the living room. She found

Pete in front of the Christmas tree.

After the services, five friends of Pete's

got together and talked about him and they wrote a poem for him.

They suspected maybe Pete had fooled everyone, and that he'd managed

to have it his way after all:

Successive series--one, two, three,

You've fooled the mob, but not fooled me.

Now deep rest and worry no more,

While the rest of us pace the hardwood floor,

Waiting for phones that never ring,

And trying our damndest to laugh and sing.

Well, Peter, we hope you've found your peace.

We, your friends, will be your wreath.

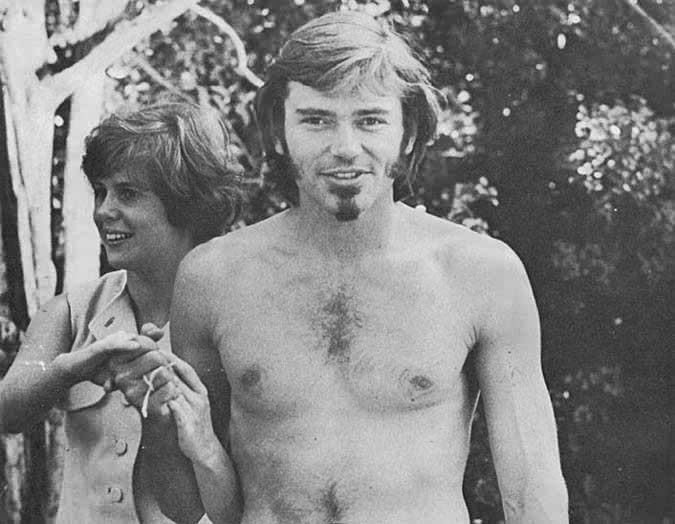

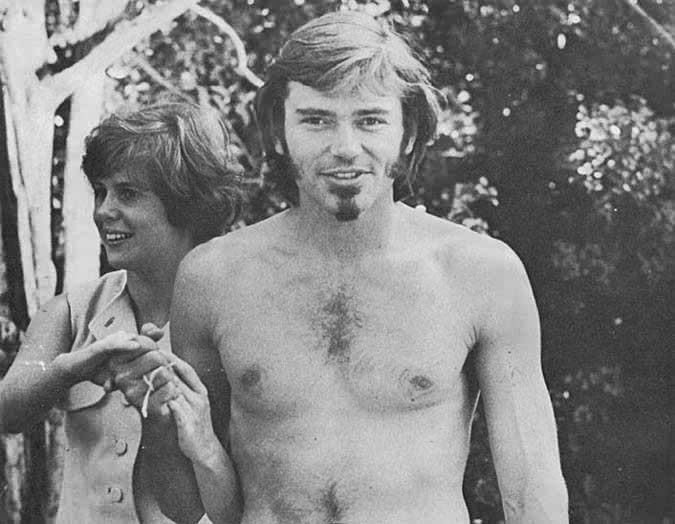

At Universal Studios, where he filmed

his television series, his drinking problem never had spilled

over into his work. It never had interfered with his reliability

or his professionalism--or his likeability.

Pete had been on the set until 7 p.m.,

working with Chill Wills and Ralph Montgomery. They had noticed

his animation and good spirits. He had been looking forward to

the New Year's weekend.

A week earlier in a burst of anger--or

futility--Pete had fired a bullet into the wall. He had been an

independent candidate for a place on the board of directors of

the Screen Actors Guild. His union had sent him a telegram notifying

him that he had not won. He had mounted the wire on the wall,

and fired at it.

It was when the police found two expended

bullets in his revolver that they briefly entertained a suspicion

of homicide. When they found out how much Pete drank that night,

they began to consider suicide.

Pete's drinking had long been a problem.

His driver's license had recently been revoked for one year because

he had been convicted of drunk driving in an accident in which

two people were injured. A few years earlier Pete had been arrested

and convicted on another drunk driving charge. Pete's remorse

and determination to conquer his drinking habit so impressed Superior

Court Judge Bernard Selber that he imposed only the mandatory

five days in jail required of a two-time drunk driving offender

in California.

It mattered to Pete that he had fallen

from grace--more than he could say and more than he could cope

with. He cared that he was drinking again, and he was drinking

again because he cared too much.

He cared that he was an actor trapped

in a TV series. Yet he knew he was lucky to have a top-rated one.

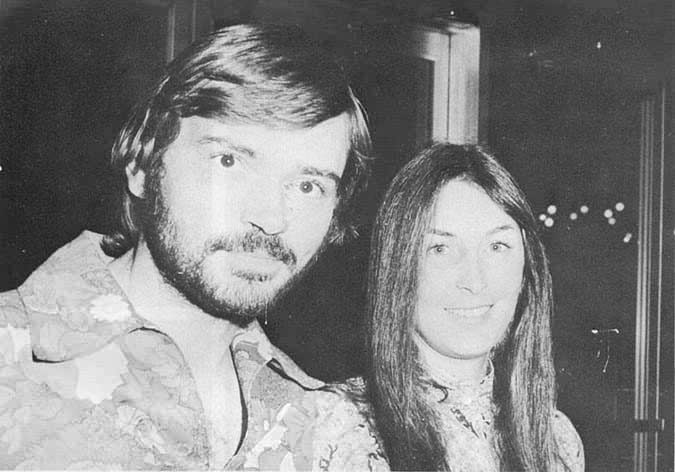

He cared that he and Diane Ray had reached

an impasse after all their years together.

However, many people thought that Pete

was still carrying a torch for Kim Darby whom he had dated for

a long time.

Whether that meant anything, or not, it

was Pete's drinking that his friends were most worried about.

"He did have a drinking problem,"

noted Jo Swerling, Jr., producer of "Alias Smith and Jones."

"I was aware of that. There wasn't too much any of us could

do about it. It was his own problem and he had to face it. We

tried to make his work as easy for him as possible. It's a grind--making

a television series.

"He was a very sensitive individual,"

Swerling reflected, "I mean his feelings were intense. Whatever

it was that affected him affected him very deeply--whether it

was something happy or something sad."

Pete's pretty sister, Pamela, who followed

in his acting footsteps, put it another way.

"He couldn't cope," she murmured.

Even before her brother died she had felt uneasy about the way

his problems had piled up. She had noticed, with increasing concern,

her brother's inability to make light of problems as others did.

His problems seemed to own him. He took them too seriously.

In the end she was to be proved right.

"Someone's got to care,"

Pete used to say plaintively.

But did Peter Duel care too much, and

the rest of us not enough? His death only asks the question but

doesn't answer it.

Back

to Articles List

Diane

screamed. A muffled, Oh-my-God, not-wanting-to-believe scream.

She faltered dizzily and the room began to swim. But somehow she

managed to reach the phone and call the police.

Diane

screamed. A muffled, Oh-my-God, not-wanting-to-believe scream.

She faltered dizzily and the room began to swim. But somehow she

managed to reach the phone and call the police.