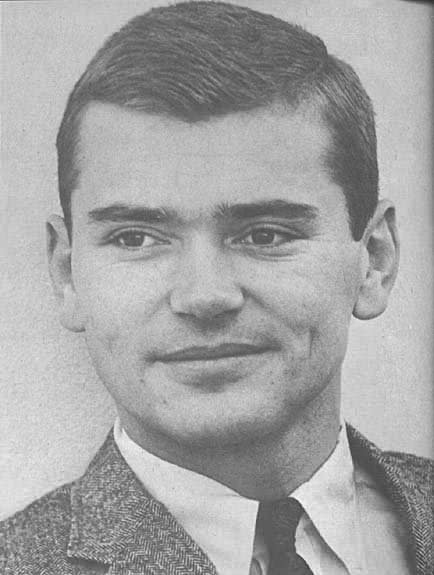

This mild looking young man is actually very dangerous.

This mild looking young man is actually very dangerous.

This mild looking young man is actually very dangerous.

This mild looking young man is actually very dangerous.

Peter Deuel comes to you through the courtesy of a guardian angel who must have the worst case of peptic ulcer in Heaven. Peter (as if you didn't know) stars opposite Judy Carne in "Love On A Rooftop" (ABC-TV); Peter's previous experience indicates that someone should be erecting a high wall around that rooftop to keep Peter from falling off.

There must be a gag somewhere in the fact that Peter is the descendant of a long line of doctors, a convenience that has saved his life several times.

However, even when he was at the measles age, he never played with stethoscope, bandages or splints; his total enthusiasm was directed toward aircraft. His first spoken word was not the traditional "Mommy," or "Daddy"; it was "P-38", the serial identification of Lockheed's twin fusillaged pursuit plane beloved by every watcher of the skies during the early days of World War II. It was quickly replaced by the P-51, a development that delighted the very young Pete. By the time he was five and the war was over, he could identify every winged object in the sky; he could specify it power, competence and eccentricities. He was already enroled [sic] in one-boy flight training.

He lazed through junior high and high school, resenting the fact that the Air Force was so archaic as to refuse to enlist a natural-born pilot during his most virile years, say from thirteen upward. Pete filled in his waiting years by tinkering with motors, attending movies, going out for school plays but exasperating everyone connected with the drama department because he abstained from learning lines. He also employed a certain amount of time in protecting a covey of local girls from the boredom of lonely evenings.

At seventeen, Pete enlisted and flunked his physical. He was a perfect specimen except for one flaw: his vision tested 20/30 instead of the prescribed 20/20. (Ironically, at the present-- nearly nine years later--Pete has 20/20 vision. The only explanation for the previous reading would seem to have been fatigue, brought on by those long hours of poring over a hot engine, or those nights spent in studying the technique of Gable, Tracy, Flynn, Harrison, Guinness, Holden, Ford, etc. etc.)

Dazed and depressed by his Air Force rejection, Pete turned his attention to speed on the ground. Or, on second thought, his frustration may not have been at the core of his subsequent activities, but rather an inherited dedication to medicine.

In the raw and bitter winter of 1958, when Pete was not yet eighteen, he and a buddy set out upon one of those trips that seem necessary to the senior in high school. Nowadays Pete can't recall the necessity, but he does remember that, at the time, it was imperative.

Snow was piled high on either side of the highway, sleet pelted the windshield and shimmered like a curtain before the headlights. Visibility ceased about a foot beyond the hood of the car. The radio was playing "Baby, It's Cold Outside."

Suddenly the headlights of another car pounced through the storm. Both cars were traveling too fast to take evasive action; they met with a deafening explosion of steel and glass.

Pete was catapulted through the windshield onto the hood. His first logical thought was that it would be easy to freeze to death in that weather, so he crawled back through the vacancy left by the disintegrated glass. The driver, meanwhile, had pulled himself from behind the wheel and was partially lying on the passenger's side of the front seat. Pete had no way of knowing it at the time, of course, but the driver had suffered a broken nose. Pete did little for plastic surgery; he sat on the driver's face.

The resultant yell ejected Pete from his perch, out the open door and into a snow drift. He noted, as he stood up, that the snow had turned red. He had heard enough about hemorrhage from the doctors in his family to realize that he had to have help--FAST. He assumed that the others in the smashup were in much the same condition.

And so, with his tongue nearly severed, and with his pelvis broken, Pete managed to strugle [sic] to the nearest open store and telephone his father.

Medical experts will tell you that the quickest known way to bleed to death, aside from slashing the carotid artery, is to cut the tongue severly [sic]. They will also tell you that the tongue cannot be sutured, because of its concentration of nerves and minute blood vessels.

However, when a medical expert is also a father, miracles must be attempted. Six stitches were taken in Pete's tongue after he was anesthetized; he was kept under sedation until the tongue, which--fortunately--heals more quickly than any other organ, had begun to mend.

Pete spent four weeks in the hospital in a cast, then spent an additional eight weeks on crutches. He was so thankful to be alive (all the crash victims survived in spite of bruises, contusions, lacerations and fractures) that swinging along on wooden horses didn't bother him. Also, he thought with a bow to his luck, a creased tongue and a mended pelvis would not interfere with his becoming a pilot. Not an Air Force pilot, of course, but a pilot nonetheless.

Meanwhile, probably as a gesture of gratitude to his father, Pete enrolled at St. Lawrence University in Canton, New York, not far from Pete's Rochester birthplace. St. Lawrence had been the alma mater of several generations of Doctor Deuels, but Pete majored in English, Drama and Psychology.

Inevitably the Deuel dimples, the old brown eyes and the cocky gait of this drama major--plus an altered attitude toward learning lines--gave Pete a chance at some fine roles. Toward the end of his sophomore year he was cast in "The Rose Tattoo," and Pete's father, Dr. Ellsworth Shaut Deuel, made it a point to attend a performance.

The following morning at breakfast, Dr. Deuel said to his son, "Peter... why don't you go to New York now and stop wasting your time and my money?"

That was all Pete had been waiting for. After auditioning and being accepted by The American Theatre Wing, he spent two years in training and in geting [sic] practical stage experience. His first network television appearance was in a segment of the Armstrong Circle Theatre; his first sight of Hollywood was experienced when he was appearing in the touring company of "Take Her, She's Mine," starring Tom Ewell.

Things have been going entirely too well for Pete, the ambulance kid. One delightful, sunny morning he was breezing down a mountain road on his motorcycle, thinking how much the experience was like flying... the takeoff thrill, the throttle back... Ahead of Peter an automobile driver signalled [sic] a right turn and swung grandly to the right. Just as Pete drew opposite, intending to pass on the left, the driver turned left and hurled Pete and his motorcycle into the canyon.

Pete knew enough about the terrain to realize that unless he dug in, lying as he was on his back, he was an odds on favorite to slide several hundred feet into the river. With that thought here came another. From where he as lying, Pete could see nothing but blue sky, the bluest sky he had ever beheld, a sky so filled with depth of indigo and a glaze of gold that it could not belong to this world.

Aloud he said in outrage, "Oh, HELL! I'm dead!"

The cliche holds that, in extremity, one's entire past life flashes through consciousness. Pete, refusing the ordinary, saw his entire FUTURE flashing before him: all the things he had planned to do and never would--the fresh water fishing, the tennis games around the world, the Mercedes-Benz he yearned to drive, the cities he wanted to visit... Beirut, Istanbul, rose-red Petra, Nauplion at sunset, Paris in rainy May...

All gone. Gone forever.

Then, on an off chance he might have made a mistake, he hauled himself to his elbows. What he saw convinced him that he wasn't dead, but that he was headed in that direction. His right leg was split open from the knee to ankle.

People who had seen the accident came to Pete's assistance, and again he was carted off to the hospital. He was in surgery for nearly three hours, then he had to endure months of skin-grafting.

"But," says Pete with a grateful wag of his head, "thanks to my helmet, I didn't even have a headache. Not at the time of the accident, and not afterwards."

After a moment's thought he adds, "Of course, one of the roughest times was when I totaled an Austin-Healy. That really made me mad... Say, is this beginning to sound like 'Dr. Kildare' or 'General Hospital?' Let's talk about something else. For instance: my collection of small lead antique cars. I have about nine now; a Bugati, a Mercedes-Benz, a Ferrari, a Corgi, a Solido... they're not easy to find, but it's a real satisfaction when you come across them."

Did he start the collection so as to have something to while away those long hours in the hospital?

"Don't SAY that. Never again," yipes Mr. Deuel.

Except... what was he doing last Sunday? Riding a motorcycle up and down one of the steepest hills in Los Angeles County.

Anyone having a spare rabbit's foot, or

a four-leaf clover from County Clare, or even a bandaid might

send same to Peter Deuel. And ABC-TV had better--as previously

suggested--run up barricades to insure the continuance of "Love

On A Rooftop."

Back to Articles List