- DARK STAR

- by Sue Weekes

- The Box Magazine, 1997

There's one thing everyone knows about Pete Duel:

he put a bullet through his head after watching himself play

Hannibal Heyes in Alias Smith And Jones. Trouble is, as Sue Weekes

finds, that may not be the whole truth...

'ALL HAVE

A great show' were Pete Duel's last words to co-star and narrator

Roger Davis as he walked off the Alias Smith And Jones set. Davis

didn't think much about it at the time. The words only sounded

significant when the show's producer Roy Huggins met him at Aspen

airport and told him that Duel had been found dead and asked him

if he would take over the part of Hannibal Heyes.

'ALL HAVE

A great show' were Pete Duel's last words to co-star and narrator

Roger Davis as he walked off the Alias Smith And Jones set. Davis

didn't think much about it at the time. The words only sounded

significant when the show's producer Roy Huggins met him at Aspen

airport and told him that Duel had been found dead and asked him

if he would take over the part of Hannibal Heyes.

Duel had died on the night of 30 December

1971 (although some reports say the 31st). He'd been at home,

an apartment in West Hollywood, with his girlfriend. He'd watched

himself in an episode of Alias Smith And Jones and his girlfriend

Diane Ray said he'd been unhappy with the show. She didn't, however,

think he was suicidal. Later that night, she was awoken by the

sound of a gunshot. She found Duel dead on the living room floor,

with a bullet hole in his head.

Suicide, decreed the coroner. Davis, looking

back, agrees. Most actors have over-sized egos and are always

worried if they're getting the best lines. Duel, in the scenes

he shot with Davis, didn't seem to bother. This set Davis thinking:

'There's an absence of ego in someone who kills himself. You have

to really not like yourself.'

Inevitably, given the odd circumstances

of Duel's death, there have been plenty of rumours about what

really happened. Allegations of murder have even been thrown about

by some fans who wish to make Duel into a martyr for the political

causes he fought for. But his brother Geoffrey Deuel [Pete dropped

the first 'e' when he got the part of Heyes] has a more plausible

alternative to suicide. As he told The Box from his home in Florida:

'Pete's death was unwitnessed and there were a lot of unanswered

questions. Pete was moody, deep and had alcohol problems. But

he was never diagnosed as a depressive. His death literally obsessed

me. I was pretty manic about it and contacted a lot of people.'

In the end Geoff laid the case to rest. 'If anything it probably

had more to do with him screwing around with guns. There was a

lot of alcohol in his body at that time.'

Suicide or tragic accident, Pete Duel's

untimely death (he was just 31) made him a legend. Over 1,000

people attended Duel's memorial service in California before his

body was flown home to Penfield, New York, where around 2,000

mourners paid their respects. He would never grow old, fat, and

face-lifted; he'd never appear in some witless sitcom; he would

always be the dark brooding presence that he was as Hannibal Heyes

in Alias Smith And Jones.

It would be easy to say, cynically, that

the only thing that's interesting about Pete Duel is his mysterious,

premature, death. But that doesn't explain why, for a man whose

legacy on film consists entirely of a myriad guest-starring roles,

some TV movies, two short-lived sitcoms and 33 episodes of a TV

Western rip off of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, should

be so fervently remembered that, on the 25th anniversary of his

death, his British fans paid for a star in the constellation of

Ursa Minor to be named Peter Ellstrom Deuel.

Ellstrom was his mother's maiden name

(she was a first generation middle American). His father was a

physician in Rochester, New York, where Duel was born on 24 February

1940. As well as Geoff, who was three years younger, he had a

sister Pamela (five years his junior) who is now a gospel singer

and runs a church ministry. Growing up, Geoff remembers his brother

'would write poetry and do these satirical ink drawings.'

Duel always wanted to be a pilot but his

eyesight was too poor so he decided to follow his father into

medicine and enrolled at St Lawrence University in Waterdown,

New York. But he hated it. The only bright spot was the college

stage plays he appeared in. After seeing their son in a production

of Tennessee William's The Rose Tattoo, Pete's dad told him to

give up medicine and become an actor. Duel moved to New York in

1960 and was accepted by the American Theater Wing for a two-year

acting programme.

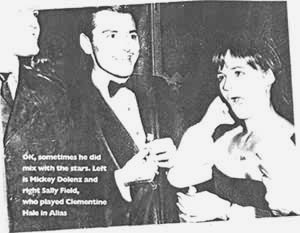

After appearing on stage he headed for

California and a small studio apartment in West Hollywood. He

got various guest spots on TV but his first taste of real success

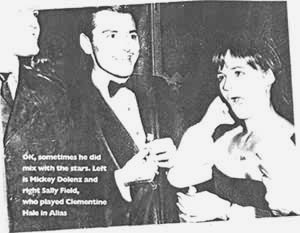

came in the sun and surf sitcom Gidget, about a girl whose father

was a widower. In the lead teenage role of Gidget was young Sally

Field, (he was reunited with her when she appeared as sometime

love interest Clementine Hale in Alias). Duel played a psychology

student, husband to Gidget's older sister, who practices on the

family. It brought him a Most Promising Male Star award from the

Motion Picture Almanac and his understated clowning in the role

impressed producer William Sackheim so much that he decided that

he wanted Duel (and nobody else) for his next sitcom, Love on

a Rooftop, made in 1966. Duel played a poor architect to Judy

Carne's posh girl. 'I was very fortunate,'said Duel. 'Love on

a Rooftop gave me a chance to be wildly versatile. It's all there,

the whole gamut in 30 or more episodes: slapstick, comedy, drama,

the rough and the tender.'

The show was cancelled after a year but

Duel made enough impact to win an exclusive seven-year TV and

movie contract with Universal Studios. Over the next few years,

he guest-starred in everything from The Virginian, to Ironside

and The Fugitive. Then, in 1970, he was offered a part in The

Young Country, a two-hour feature Western for ABC in which he

played alongside Roger Davis. 'I was in the tradition of Gary

Cooper, 'says Davis, 'whereas he was more Machiavellian. We had

great chemistry.'

After his performance in The Young Country

came Alias Smith and Jones, created by Glen A Larson. The tale

of two good-looking, lovable reformed outlaws was an obvious spin-off

of Butch Cassidy and The Sundance Kid. Hannibal Heyes and Kid

Currie had been given a secret pardon by the Governor of Kansas,

as long as they could stay out of trouble for a year. This wasn't

going to be easy as they still had a price on their head. But,

as the voice-over at the beginning of the show always reminded

us, 'in all the trains and all the banks they robbed, they never

killed anybody.'

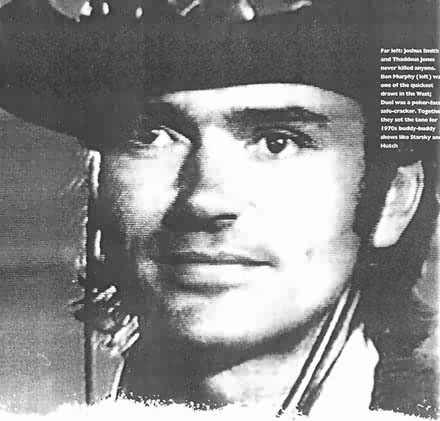

The series was far more irreverent than

the TV Westerns which preceded it, like The Virginian, Bonanza

and The High Chaparral, and set the tone for much of the male

bonding that was to follow on American television in '70s shows

such as Starsky & Hutch and The Dukes of Hazzard. The chemistry

and quickfire exchanges of dialogue between the Duel and Murphy

carried the show. The tone was set by an exchange in the opening

voiceover: 'There's one thing we gotta get Heyes? 'What's that

Kid?'' Out of this business'. This tone enabled Alias to buck

the shift towards cop shows, making it American television's last

primetime Western hit.

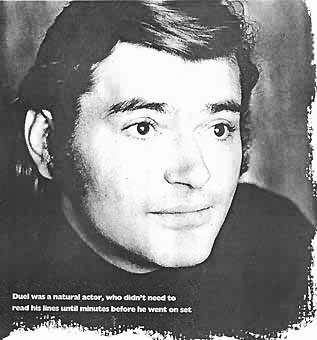

'Pete had a wonderful look on screen,'

says Roger Davis, who had one of the hardest jobs on TV when he

took over as Hannibal Heyes after Duel's death. The ratings didn't

slide although Davis lived very much in Duel's shadow: 'There

were people on the set who would never let me forget it.' One

of those people was Murphy who came up to him years later and

said if he'd realised Alias was the best thing he [Murphy] would

ever do, he'd have been a lot nicer to Davis.

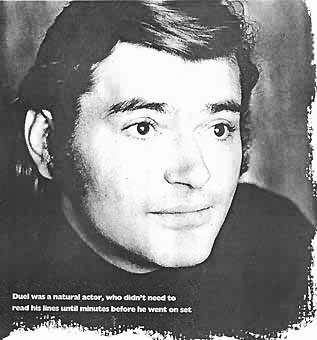

This was exactly the kind of egotism Davis

never got from Duel. 'He was a complete natural,' he says of his

late co-star. 'He didn't even have to learn his lines until just

before he went on. Such a complete absence of nerves gives you

great strength as an actor.' He particularly remembers the episode

Smiler With A Gun, in which he co-starred as a villain. 'Pete

and Ben were at a poker table and Pete had the script on his lap.

He kept having to get up and in the end just let it fall to the

floor and got on and did the scene. It was great ensemble acting.

Nobody wanted to let the other two down and Pete knew he could

always rise to the occasion.'

But his brother Geoffrey says it wasn't

long before Duel felt trapped by the show's success and began

to talk about 'jumping ship'. He'd begun to feel restricted by

the shooting schedule which didn't give him the time to pursue

his favourite hobby, camping alone in the wilderness. It was probably

about this time that he began to argue with script writers. His

brother recalls: 'Pete could play things on different levels.

He had an uncanny sense of honesty which is partly why the kids

related to him.' That sense of honesty spilled out into his life

outside showbiz. Although film stars like Paul Newman were politically

active in the late 1960s, TV actors weren't supposed to emulate

them. But Duel did: he supported and worked for the Democratic

presidential candidate, Eugene McCarthy (known as 'the peace candidate')

in the 1968 primaries. But Duel was just as committed to a less

fashionable cause, the plight of America's native Indians.

'I remember going to his house once and

he was playing this song Indian Nation incessantly,' recalls Davis.

Duel's house and lifestyle eschewed the usual Hollywood glitz

and glamour. 'He had a rustic apartment and liked to spend time

alone with his dog,' says Davis. 'The dog and the Indians were

both part of this affinity he had with people and things which

weren't on top. His lifestyle wasn't typical of that of most actors.'

Inextricably linked to this was Duel's

own melancholia, which was completely at odds with his 'cute and

charming' on-screen image, according to Davis. 'He really didn't

handle the highs and lows very well,' he says, suggesting a reliance

on uppers and downers. His habit of driving under the influence

eventually led the authorities to ban him from driving.

As his private life became increasingly

problematic, his public life went from success to success. Cashing

in on Alias's popularity, ABC re-ran Love On A Rooftop in the

summer of 1971 and aired a TV movie called How To Steal An Airplane,

which had been acquiring dust for some years. He took time off

from the show that summer to film a version of the stageplay The

Scarecrow in which he co-starred with Gene Wilder. He claimed

that this was the work he was proudest of. The exhilaration didn't

last very long. Only a few months later he left the Alias set

for the last time bidding a casual, but chilling, goodbye.

The BBC can't decide if Alias Smith and

Jones will still be running when you read this. Thanks to Jan

Bushell of the Pete Duel Memorial Club for the the pix. Those

wishing to join should contact The Box and we will pass on any

enquiries. If you want to reach the Alias Smith and Jones web

site, the address is www.panix.com/~menikoff/alias.html

Back to Pete Articles List or Geoff Articles List

'ALL HAVE

A great show' were Pete Duel's last words to co-star and narrator

Roger Davis as he walked off the Alias Smith And Jones set. Davis

didn't think much about it at the time. The words only sounded

significant when the show's producer Roy Huggins met him at Aspen

airport and told him that Duel had been found dead and asked him

if he would take over the part of Hannibal Heyes.

'ALL HAVE

A great show' were Pete Duel's last words to co-star and narrator

Roger Davis as he walked off the Alias Smith And Jones set. Davis

didn't think much about it at the time. The words only sounded

significant when the show's producer Roy Huggins met him at Aspen

airport and told him that Duel had been found dead and asked him

if he would take over the part of Hannibal Heyes.